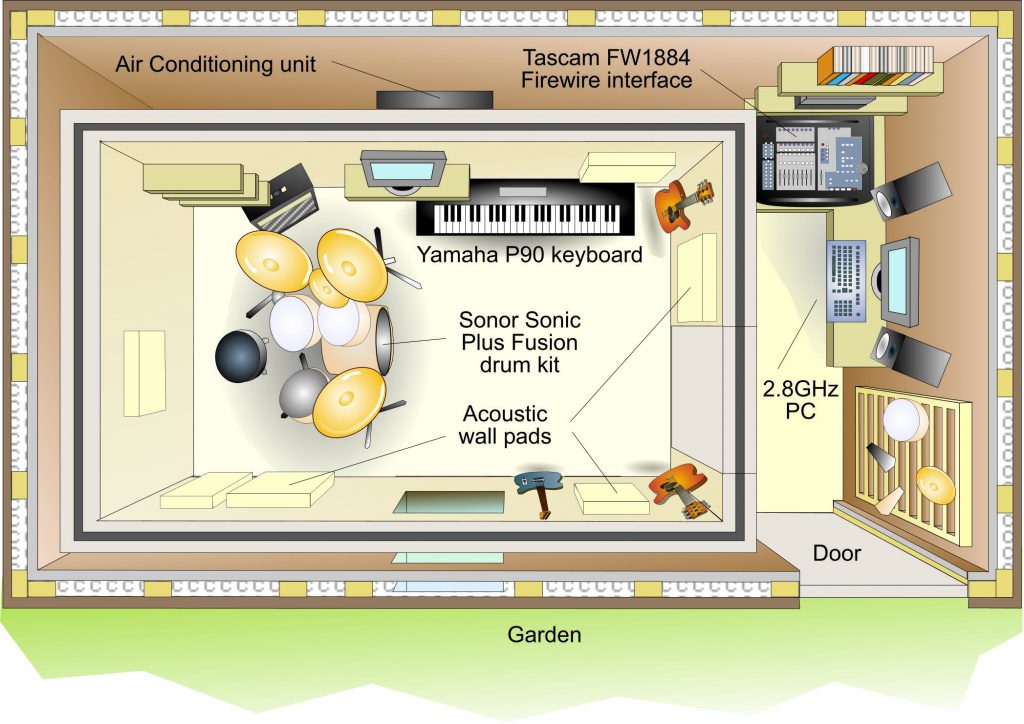

Alan Pagan’s shed, situated in the back garden of his London flat, is a home-made structure designed to accommodate a professional sound-proofed recording and practice room for drums and other instruments. The shed superstructure also incorporates a small control room with recording and monitoring equipment, plus some vital overhead storage space for the cases and accessories required for gigging work.

“I wanted the studio primarily for drum practice,” explains Alan, “so I could really work on getting the right setup and preparation for the various gigs that come in. Occasionally I’ve been caught short and failed an audition because I could only practice on an electronic kit.

“Now I can work on my drums properly, get my sounds right, get demos together for various projects and use my recordings to generate gigs. For example, recently I used it to record a demo for the Brazilian trio I play with, we sent that off to agents and they’re now getting us gigs. We had to produce the recording in less than two weeks which would have been a pretty tough schedule if we were trying to book a nice-sounding studio and get everyone together at the same time with a recording engineer. Having this set up means there’s no hassle, and it’s a catalyst for getting things going.”

Shed Experience

Alan first dreamt up the soundproofed shed idea back in 2004 when he and his younger brother David were given the opportunity to buy a flat with its own garden. David, also a musician and composer, was keen on the idea of building a studio too, so the pair pooled their resources and purchased the property.

One of the first things Alan had to do was speak to the council to ascertain what planning permission restrictions they would face when erecting a building in the garden. Indeed, the structure was subject to certain planning limitations governing its height, width and depth, and it could only occupy a certain percentage of the garden. Part of the allowance had already been used by a conservatory so Alan’s structure was fairly restricted. Thankfully, it being merely a shed as oppose to a home extension, building regulations were not an issue.

Perhaps the easiest option for Alan and Dave would have been to buy a prefabricated shed from a retailer, but a cash-saving alternative was to source the raw materials and make the shed themselves. Fortunately another of the Pagan siblings, Daniel, was able to offer his skills in designing the framework, and his time putting it together, so they decided to take the DIY approach. “I started applying for planning permission back in June 2004,” Alan remembers. “It can seem an intimidating process at first, but I started by getting the official street layout to the required scale from the Multimap web site, and that showed my house and the size of the garden. My brother Daniel helped me draw the various elevations of the shed and its proposed situation in the garden.”

Alan’s initial idea was to build the shed structure and soundproof its walls, but after speaking to a few people he realised the only viable way to quell the sound of drums was to buy a specially designed sound booth and fit it inside. The choices were restricted by both the size of the shed and Alan’s budget.

“I had a lot of preparation time while the plans were being processed, so I just kept asking people for advice until I found the best and most affordable solution. Someone suggested the Esmono booth from Studiospares but, after speaking to Studio Wizard, I went for a product called Soundblocker made by a Berlin-based German company of the same name (www.soundblocker.de). It just seemed to me that they were offering a little more for the money. For example, a basic Esmono doesn’t come with a floor and a window is extra, so the basic package is not inclusive. The Soundblocker, on the other hand, has everything included in the price.”

Initially Alan simply wanted a room for his drums, so his first thought was to have a booth that filled the shed completely. Eventually the plan changed to accommodate a small storage area to keep gigging equipment and cases, and that finally evolved into the concept of having a bijou control room alongside the booth. The only problem was fitting everything into the strictly limited space!

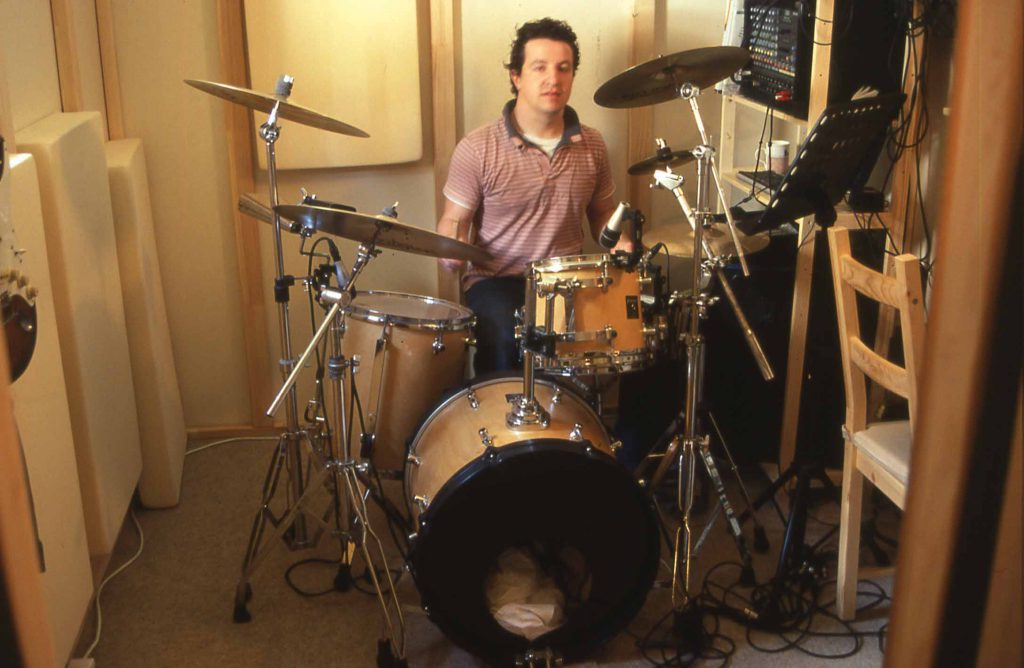

“Although I had to get something small, I made sure it would have ample room for the drum kit plus some space at the side so that if I’m seated facing into the room I can still get in behind kit and out again. If there’s too little room you end up pointing the kit at a wall, and then you need a mirror to communicate with the musician behind you! I’d seen that scenario in other studios and wanted to avoid it, so I carefully went over and over the plans to check everything would fit. The interior of the booth is about two meters 20 by three meters 60 so there’s enough space to comfortably fit me plus three other musicians, and it can just about accommodate six of us at a squash.”

Footprint In The Garden

Through communications with Soundblocker, Alan had learnt that it was possible to assemble the booth inside a small space, so he decided to erect the shed first and fit the booth afterwards. The first part of the building project was the construction of a concrete base, comprising three inches of hardcore followed by a further three inches of concrete. “It’s recommended that you place the damp proof membrane on top of the hardcore before laying the cement layer but it was horrific weather when we were laying it down so we more or less forgot to do that and ended up with the membrane on top of the concrete,” admits Alan. Because there isn’t easy access to the garden I couldn’t have the concrete poured directly from a lorry, so I mixed it myself by hiring in a portable mixer and taking it through the house. The mixer, cement and sand cost me between £200 and £300.”

“I sourced the wood and material from the builder’s merchant Travis Perkins. David and I had roughly worked out the quantity of wood, nails and screws we’d need, but they were actually able to specify a quantity of each based on my measurements.

“The frame is made of three by four-inch timber and that is clad in shiplap to seal the outer walls. The roof is pitched for drainage and covered with roofing felt. It took a week to build the basic structure with my brother Daniel, me, and some friends, working every day. I started layering the shiplap between other jobs, and that took another two weeks. Then it was a matter of putting insulation between the frame timbers and adding a lining of hardboard.”

Alan’s next problem was getting his booth to the UK. The delivery charge was going to amount to over £1000, which would have wiped out the budget for equipping the studio. Instead Alan hired a VW Luton van and, with help from Daniel, drove to Berlin to pick it up himself! “The van cost about £600 but I found out that the company David works for needed some theatre sets taking to Berlin and, at the same time, their lighting engineer was moving there and storing the theatre sets at her house, so I ended up exporting both the sets and her stuff, and that pared the costs right down to about £300!”

In Berlin, Soundblocker’s staff were helpful enough to load the flat-packed booth into the van, but back in London things would prove to be considerably more difficult, as each part of the assembly had to be manoeuvred through the flat to the back yard.

Alan: “We picked up the Soundblocker booth at eight am, drove all day Monday to get home at two am in the morning, so we went to bed exhausted. The problem was that the van’s back doors didn’t lock properly so I couldn’t sleep and kept checking for thieves every hour. As Daniel was only available for the Tuesday and Wednesday it was straight to work in the morning!”

Initially Alan and his friends had to decide exactly where to place the booth within the shed structure. Soundblocker’s instructions were to leave a certain amount of room for the ventilation system but the space also had to be large enough for a person to squeeze through to fit and maintain it easily.

Alan and Daniel began by laying the supplied foam blocks onto the waterproof polythene membrane. “Although they’re soft, they spread the weight very well if you have enough down,” explains Alan. “On top of them we laid the two layers of floor, and then started building an outside corner according to the instructions. When that was finished we made the inside corner and sandwiched slabs of rockwool in-between. It was the same routine for the walls, and then the ceiling helps hold the structure together.

“The boards that form the walls are made from a very dense type of chipboard, coated in a hardened cream-coloured surface. Each slab is about two foot wide, and there are about 13 of them on both the inside and outside. All the panels slot tightly into a timber frame so that the whole structure bonds together under pressure, pretty much without any nails or screws.

“We got the booth set up by Wednesday afternoon having picked it up in Berlin on Monday, but then fixing the acoustic tiles on the ceiling, adding door handles, rubber seals, laying carpet tiles and installing leads through the portal to the control room all took me another week and a half.”

Proof Of The Pudding

Alan seems pretty happy with both the quality of the sound inside the booth (which he describes as ‘nice and warm’), and with its soundproofing attributes. “It cuts out all but the lowest frequencies,” says Alan, “so you don’t hear any cymbals; you get a tiny bit of bass drum, almost no tom, and no snare at all. The walls are slightly reflective, so it’s not totally dead but I didn’t want something that soaked up all the sound straight away, as that tends to feel very dead, which isn’t very stimulating. The model type I have is called AS, which is the middle option, recommended as a mix-down and practice room. It comes with foam pads that you can place on the walls if you want a little more sound absorption or deadening, and there are modules that fix on the ceiling that provide a degree of acoustic modelling. I also opted for active ventilation instead of passive as that reduces sound leakage.

“There was the choice of a more expensive option called SP that has the highest absorption of sound and is ideal for drums, and a basic one called MA which doesn’t have any acoustic modelling – it’s just a soundproof room suitable for instruments like flutes, violins and trumpets.”

Although the booth satisfies Alan’s initial desire to have a room in which he can practice drums properly at any time, the addition of a recording and monitoring area has turned the shed into a mini production studio. Alan’s Sonar Sonic drum kit and assortment of cymbals and percussive instruments are recorded using a set of Samson 7 mics fed through to the control room and into a Tascam FW1884 preamp/digital mixer which interfaces with Alan’s 2.8GHz PC via Firewire. Recording on the PC handled by Steingberg’s Cubase using the standard bundle of plug-ins. “We were thinking of getting an 01X first of all, instead of the Tascam, but that only has two XLRs, whereas the Tascam has eight so it is better for drums,” explains Alan. “My friend, Martin Garfoot, who trained as a sound engineer on the same music course as me in Salford (see the Alan’s Story box), set the levels while I was drumming, and has saved some scene templates we can recall. The preamps are not fantastic, so at some point we’ll probably get some valve ones for things like lead vocals. I’m also hoping to get some more plug-ins for Cubase to expand the software side of things. My latest addition to the studio is a second TFT monitor and remote keyboard so I can operate Cubase from within the booth, and that’s working out really well.”

Final Thoughts

As you’d expect, the studio has been in constant use since its completion, providing Alan with some satisfying results along the way. Co-owner, David Pagan, has also found it an ideal base for composing and preparing songs for the various productions performed by his theatre company. First and foremost through, the studio is enabling Alan to fulfil his aim of becoming a better drummer. “It is allowing me to practice the drums, but I’m finding it is a good a storage place as well, and as far as recording is concerned, it will allow us to record some new projects and get demos together. Good demos will generate work outside of the shed, and hopefully that will be good for my career.”

Post Script: Alan’s Story

“I started drumming using a few biscuit tins, but I got my first drum kit when was about 11. I loved its impressive sound and found that I could improvise without having to learn chords or scales. In that respect, drums seemed different from something like a piano where you have to get each note exactly right. I began teaching myself and spent my holidays going through various drum books.

“When my older brother Martin bought an electric guitar and little Marshall amp we created a metal band and gigged around the local pubs, helped out by some older guys who played in a local thrash metal band. My younger brother David became our lead vocalist.

“Martin was the first to get onto the music BA Honours course in Salford, but when I visited him at the college to record some of our songs together with his colleagues I decided I had to do the course too. I loved being in the studio and getting a near professional sound. I went there straight after college, having got the necessary music grades, and took the popular music course which included composition and performance. I had drum lessons, did lots of recording and gigging, and found that learning to share ideas and work with others was a good experience.

“Afterwards I returned to London with a band called Archangel, having been advised that the city had more opportunities, and landed a job in the keyboard department of the Eric Lindsey Music shop in Catford. I’d used audio sequencers at university but I found that I still knew relatively little about technology and hardware. I had to learn to use the equipment and understand how basic computer studios are set up, so I read lots of manuals and got to know what the possibilities were.

“Before building the studio I was playing in function bands doing loads of weddings and not really balancing it up with making original music. I thought about giving it a rest and even began studying physiotherapy, but that made me realise that I missed the drums, and since then I’ve rebuilt my career, got back in contact with drummer friends, musicians and band leaders and have been scouting for gigs. Now I’ve got lots of different sources for gigs and a nice balance of activities. I’m also working as a peripatetic drum teacher in schools.”

Main Gear

Sonor Sonic Plus Fusion kit.

Assorted cymbals including Zildjian, Sabian, Istanbul, Paiste and Ufip.

Tascam FW1884 digital desk.

Compaq Computer, 2.8GHz, 80GB hard drive.

250GB Iomega external backup drive.

Samson 7 Kit drum mics.

Roland TD6 Drum Brain.

Rextron Video Splitter.

TFT Monitors (x2)

Audio Technica 4033a condenser microphone.

Yamaha Click Station.

Fender Stratocaster.

Yamaha bass.

Yamaha P90 keyboard.

Laney L50 bass amp.

Marshall Valvestate 40 Guitar amp.

Leem Pro 104 Powered mixer.

AC Euro monitors.

Yamaha NS10 monitors.

Evolution MK149 controller keyboard.

Samson Servo 170 power amp.

Dbx 286A compressor

Proteus 2000 sound module.