Currently living and working in Beirut, Tom Young explains what it takes to survive as a painter and gives his view, as a European, of life in the turbulent Middle East.

“I’ve never been to a place so misrepresented in the media,” insists Tom Young, speaking about Beirut in particular, and Lebanon in general. “The media image of the place is different to the reality. Obviously there can be trouble and conflict here but it’s really not as bad as you might expect.”

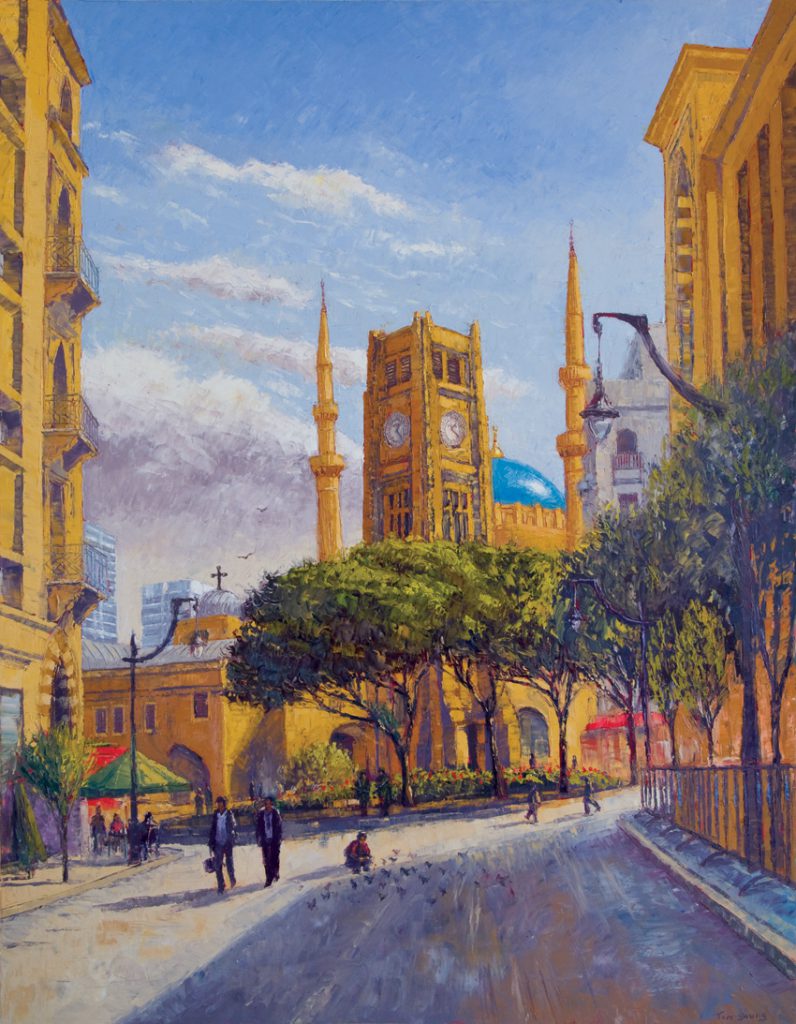

For the last few years Tom has made Beirut his home, having spent most of the previous decade living and working in West London. His work is mainly impressionistic, strong on colour, texture and contrast, and his preference is to paint his environment as he finds it.

I was lucky enough to meet Tom when he was on an Arts Foundation course at Norwich School of Art in the early 1990s. Although he went on to do a degree in architecture, more than most students I knew, he seemed destined to one day become an artist. While most people concentrated solely on their courses, Tom was extremely active outside college. I recall him spending several freezing winter evenings in his tiny red VW Golf, painting a night scene of our local corner shop – a picture he later sold to the owners. Another time he took residence in a pub, painting the pool players and locals.

One of his most striking paintings, I remember, was of a gnarled tree in dense woodland, its roots bursting from a bank and covered in moss. He completed the huge canvas on location over two days, leaving his picture and easel on site over night, sure that no one would venture that deep into the trees and find it.

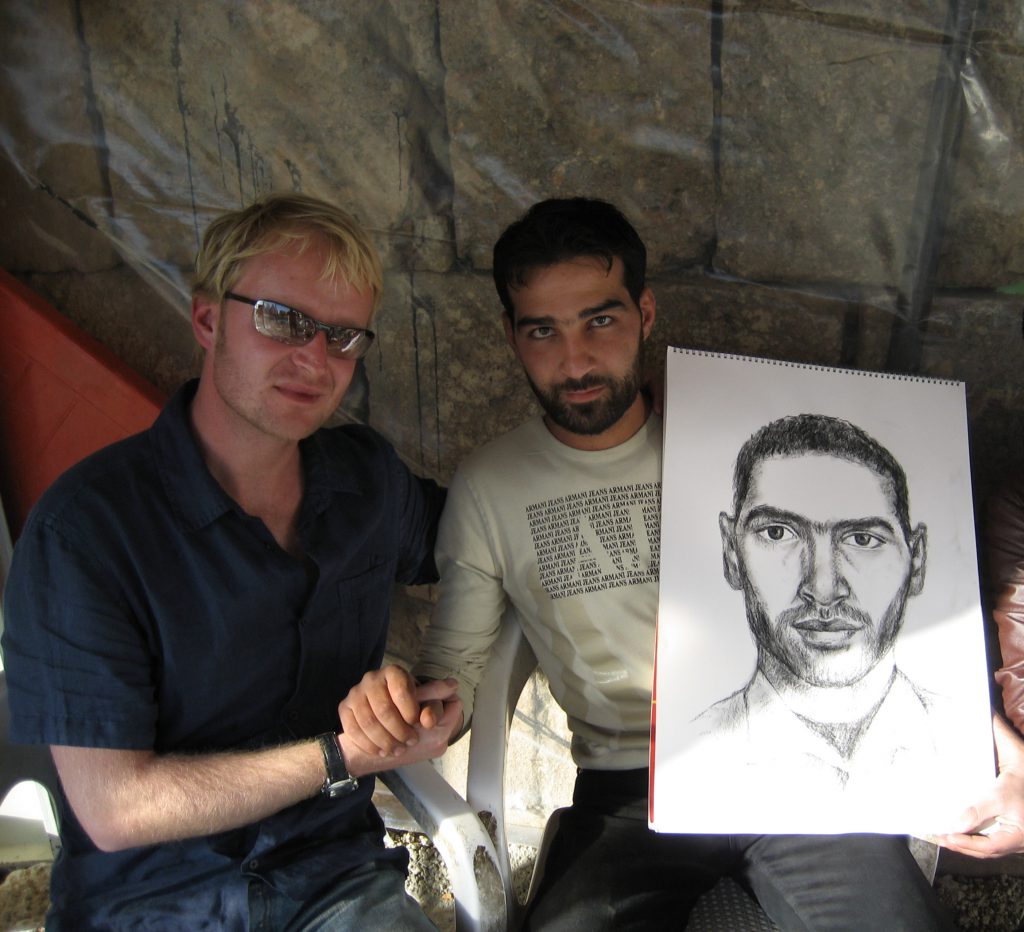

Whatever the location and weather conditions, if Tom had the desire to paint, he would follow it. And whenever I’ve met Tom since those days, one of the first things he has done is open up his sketch book and tell the fascinating story behind the creation of each picture inside.

Over the phone, Tom relates one particular incident which happened while he was doing a sketch outside the parliament building in Beirut’s Town centre. “I was doing a symbolic painting of a church and a mosque together when this very heavily-armed soldier came up to me. He was guarding the parliament building and I though ‘Oh no, he’s going to tell me to go,’ but actually, to my surprise, he really wanted to see my painting and ask about my techniques. He was fascinated by art and it turned out he knew quite a lot about art – particularly renaissance and impressionist art. There he was, with his big machine gun, talking about the delicate issues of the history of art, and he even knew some Shakespeare.

“Then a man, who was selling ice cream from a shop on the parliament square, came out from behind his counter to see what I was doing. It turned out he was also very interested in art and a bit of a painter himself, so he started asking me about my technique too.

“He seemed to think that I was using a certain technique for a certain reason and the soldier started disagreeing with him. Eventually they began having a bit of an argument about it!

“And so I had to stop concentrating on the painting and tell them both exactly what I was doing and why I was doing it. It’s the first time I’ve had to intervene in an argument between a soldier and an ice cream man! Then we all laughed and agreed and the ice cream man went and got us some free ice creams.

“Very funny things like that happen a lot here. You get into all sorts of situations. I’ve had one or two incidents where I’ve had to watch it. People have asked me one or two questions on a security level but, on the whole, some of the sweetest and funniest times I’ve experienced have been painting on the streets.”

Falling For The Middle East

Tom’s relationship with the Middle Eastern countries started when he visited Israel and Palestine as a child. The memories stayed with him, so later, when he landed a commission from a Jewish family to make a painting of the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, he leapt at the chance. It was entirely coincidental that a couple of years later, a Lebanese family living in London asked if he could do a painting of their homeland.

“They’d seen my paintings of Italy and France and the landscape of Lebanon is not unlike the south of France or Italy. So the person who commissioned me asked me to go there.

“Working for opposing sides was really interesting politically, but I was already aware of the issues. I’d read a lot about Britain’s involvement in carving up the Middle East, thereby creating a situation which now leads to a lot of suffering. I was very interested in what my country had done, which was mostly bad, although there have been individuals who’ve done positive things as well. So there is that connection with my homeland.

“Also, after September 11th 2001, most people’s lives were changed in some way and, as an artist, I was thinking about how I could engage with the issue of East versus West and the so-called ‘clash of civilizations’. Clearly that is a massive generalization, because it is not as black and white as that, but I was wondering what was going on in the world, reading about it in newspapers and trying to respond to it as an artist.

“I recognised the importance of trying to bridge gaps, and with the invasion of Iraq it seemed to be becoming more and more important to connect and try to understand what was going on. So when I got the Lebanon commission it felt like a real Godsend because Lebanon is a place unlike any other in the world. You could say it’s a unique place where Western civilisation meets Eastern civilisation– it’s half and half.

“As well as all these ideological considerations I also had to consider if it was a good place to do business, and it is one of the best places in the world to do business. The Lebanese are very interested in buying, selling and investing, and very good business people.”

“I came to do the commission in the spring of 2006 and that’s when I really engaged with the area. While I was in Beirut I got a few more commissions from people who loved what I was doing so I stayed on. I really loved the place, made some friends, went to parties and planned to come back in the summer.

“But the day my flight was booked was when the Israelis bombed Beirut airport. So just after I’d discovered this amazing land it got attacked. I knew a lot of people who were in the firing line. I also, curiously enough, knew quite a few people on the other side. So it was inevitable that it led to me being more engaged with the country.

“When the war started I thought, ‘What can I do? I’m not a politician, soldier or doctor, so what can I do to help?’ I decided to come back and do workshops with children who had suffered during the bombing. I was teaching these poor little kids in areas where there were bomb craters. I suppose it was art therapy for them, but they actually taught me a lot as well. It amazed me how they coped with the terrible things that had happened to them. Some had lost family members. So it gave me a different perspective on life and what really constitutes a problem.”

Compare And Contrast

Contrast is one of the key themes in Tom’s work, and there are few places which offer such striking contrasts as modern-day Lebanon. “The contrasts of joy and pain, beauty and ugliness are magnified here. I think that is why I like painting in Lebanon so much. Out of all the places I’ve been to in the world, this is where contrasts of life are most graphic.

“It’s difficult to say exactly why, but I think it’s just that Lebanon is blessed with sublime natural beauty, in terms of the landscape, the location, the climate and the light. In all those respects it is virtually second to none. But because of its location in the world it is fought over, so the traces of conflict and war are very visible.

“Things aren’t gentrified as much as they are in Europe. For example, the Lebanese don’t tend to clean up their mess very quickly so a lot of the buildings weather very naturally.

“This is because the country runs on private enterprise – there isn’t really any Europe-style state control – so unless someone chooses to develop a ruined building site, it just stays like that for years. But it does allow for a very exciting visual chaos, in terms of the contrast of new, unregulated developments appearing alongside the old architecture and beautiful scenery.

“On the negative side there is no heritage industry worth speaking of, so a lot of old buildings get pulled down to make way for private enterprises. So, for me, there is an extra urgency to paint that contrast before re-development or another conflict happens. That said, there are private individuals who are preserving and renovating old properties.”

Heading East

Working freelance is stressful for anyone, but being an artist is particularly difficult. Tom has managed to live from his art alone since 1997, although he started winning commissions on a regular basis as soon as he left university a year or so before. On occasion he has supplemented his earnings teaching life drawing, but in recent times his teaching has been purely for charitable reasons: running the aforementioned art workshops for disadvantaged children.

For Tom the hardest thing to deal with as a freelance artist is uncertainty, and that feeling was most acute when he worked in London. “Being skint and not knowing how you are going meet next month brings with it a lot of tension and anxiety. When I was living in London that was horrible and I’m very glad I don’t have to deal with that anymore. My finances are much better here.

“It was also difficult accepting the limits that the necessity of selling put on my own freedom as an artist. For example, there was a gallery in London that I was working with, which was selling a lot of a certain kind of picture that I was doing, and they just wanted more of the same. I needed the money so I had to do it. I tried to make each picture subtly different because I think the real challenge is to maintain your integrity as much as you can, even though you might have to make some compromises.

“It’s all about keeping your artistic spirit alive and not being turned into a machine by the market. That’s the thing. And now, thank God, I’m out here. I’ve more space, peace of mind and freedom to really experiment and push my boundaries.

“But I never would have got all of the work that I got, or the international contacts, had I not been in London. So London caught me in a kind of paradox. I had to be there to do what I do, but I couldn’t stay there!

“There is definitely a kudos attached to being British which does work in my favour. People in Beirut love Europeans, particularly if you are a European who chooses to live in Lebanon and celebrate its beauty. A lot of foreign people come just to concentrate on the dark side, and the locals don’t respond very well to that. Most foreigners are either journalists fishing around for trouble, desperately wanting the next conflict to start, or NGOs – Non Governmental Organizations – many of which do a good job but are basically only here for that purpose.

“I have seen the darker side and worked in situations which are trouble but most of my work is trying to look on the positive side and perhaps change a few stereotypes that people have about the Middle East, and particularly Lebanese people.”

Out With The In Crowd

One of Tom’s favourite subjects is the city landscape. Before he started documenting the sights of Beirut, for a decade he based himself in West London near the Thames, where he could easily reach a great number of iconic landmarks such as Battersea Power Station and the Albert Bridge in Chelsea. Although the area was good for trade, in terms of selling paintings to the cities most affluent, it was some distance from the home of the London’s elite art crowd. Tom explains his reasoning for living West rather than East.

“I think being in the West did matter. Although it’s a very untrendy place in terms of the art world, it helped because there are a lot of cosmopolitan and wealthy people in West London who liked the fact that they didn’t have to go too far across the city to see my work.

“I’d attract a lot of Lebanese, Palestinian, Jewish, Italian and French people with money, who seemed to hang out in West London. The cool, trendy art crowd, on the other hand, are in East London, which is very exciting artistically, but financially not very worthwhile. I often went to East London to see my friends who were based there and keep in contact with what was going on, but it wasn’t the place for me.

“Maybe if I had lived there my career would have gone in a different direction and I’d be making conceptual installations in Norway! Who knows? Maybe I’d be best buddies with the Chapman brothers and going to celebrity parties.

“Much as I like quite a lot of what people like the Chapman brothers and Damien Hurst do, my art is really nothing to do with what they are doing. I think my art is more traditional. It’s not for the rarefied, elitist market, or those with millions to spend. I like my art to speak to the ordinary Joe – the man on the street.

“I was inspired by Damien Hurst and the Chapman brothers in terms of engaging with the themes of life and death, but as a painter I’ve chosen to work in situations where you see those big issues being played out, rather than staying in a studio in East London.

“That is my attitude to art and life. I try to get close to the source of the issue. But although my way of working is direct, the techniques that I use are more traditional and rooted in impressionist painting, and there’s also quite a bit of narrative symbolism in my work.”

Counting The Cost

Tom may be a very passionate and accomplished painter, but it is also his ability to get on with people and do business which has enabled him to earn a living as an artist. Correctly pricing work and managing the costs of travel and materials are all things which an artist has to get right in order to get by.

For a while, Tom was making his own stretchers, but although the process saved money, it proved to be very time consuming. “I had to drive to the saw mill, get the wood, have it cut to the appropriate angle, chop it up, screw it together, then stretch and prime the canvas. Maybe it would only cost me £50 to make a canvas but it would be two or three days work and I’d have to count in the transport costs and labour.

“I do sometimes stretch and prime my own canvases here in Beirut, but it’s because I want to use specific local materials rather than as a way to save money. For example, I’ve been painting on some fabrics I bought from the market, which have some interesting patterns. Here I can get a really good-quality medium-sized 100cm by 120cm stretcher, and canvas stretched on it, made for about £30, whereas in London it would be more like £150 to £200.

“As for paints, a tube of oil is about £10 and I generally use about seven different colours. I only use a small part of each tube per picture, so it probably works out at about £20 in paint. As for travel, I do a lot of my work in my studio here in Beirut, but if I’m doing a commission somewhere in the mountains I’ll have to count in the car hire. If I need accommodation I charge it to the commissioner, or sometimes they put me up in their house.

“But when I am doing a commission in a foreign country – I’ve done commissions in Italy, France and Morocco, for example – I’ll try and build that into the cost of the whole job. And sometimes, if the people who commission me can’t afford much, I’ll do about five or six paintings on the trip and let them choose one, and possibly a second to please the misses! Then I’ll have four or five big canvases left to sell. So it does pay off in the end, but sometimes I don’t see a profit for a few months.

“The gallery in Beirut that represents me are selling my work for twice as much as my London gallery sold my work, but the cost of living is about three times less. And they take only 38 percent as oppose to 50 percent. So in just about every respect I am better off working in Lebanon. But if you really hit a big market in London, which I didn’t, then obviously it becomes a different ball game altogether.

“In a day I can do a decent size oil measuring about 60cm by 80cm, if all goes well, but sometimes you need to do what you can in a day and then live with it for a bit before completing the picture. The biggest canvases take quite a few days – sometimes a week or two – depending on the complexity of the composition.

“Sometimes I price them on the size, but the quality of the picture also matters, and sometimes a small picture is just leaps ahead.

“I keep on thinking that I’d like to paint bigger but maybe I haven’t quite got the confidence yet. I tend to sell more medium size pictures, but I sold a pretty big one here last week, measuring one 150cm by 120cm, and that will pay for most of my year, or at least the next few months.”

Tools Of The Trade

After many years travelling around, sketching and painting from life, Tom has refined his artist tool kit so that it includes everything he needs for a variety of jobs, but remains portable. He explains what comprises his essential gear. “I always have my pallets, the range of oil colours that I always use; coloured pencils, all sharpened and in a little box; soft pastels; a set of oil bars – which are big oil pastels; gouache and water colour paints; and inks for sketching.

“When I sketch I generally put down watercolour, ink and gouache first, then add pastel on top of that. I use the pencils to tighten it all up at the end. Using multimedia for sketches enables me to achieve the right textures, colours and tones very quickly.

“I sketch on A2, which is quite big size, but that is so I can let my hand go free. If I’m just sketching with one colour, I like to use a Conté Sanguine, which is a mixture between a pastel and a pencil. It has a very warm terracotta tone.

“When I’m sketching out on the street I have the pad of paper under one arm and everything else in a little shoulder bag, plus a folding fishing seat to put down wherever I am. Maybe I’ll sometimes have a little sandwich in the bag, but I often get something to eat where I am. My sketch book, pencils and pastels are all that I need, the rest is out there.

“I like to remain open to the sounds and the smells of the city and not shut myself off, so I don’t usually listen to music, unless I purposely want to shut myself off for some reason. But in the studio I always listen to music. I’ve got a big music collection on iPod.”

“Sketching cities is particularly good because you pick up all sorts of stories from passers by, particularly in a very friendly place like Beirut. People come up and talk, telling me stories about the history of the area. In fact people often give me coffee and cake and if I need a place to sit they sometimes help me out with a chair.”

When asked if the same hospitality would be offered to a painter on a London street, Tom’s answer is unequivocal. “No, you often get told to piss off! So Lebanon is a brilliant place to paint, because of the friendliness and hospitality of the people and, going back to what I said before, they are pleasantly surprised and amused to see someone painting instead of some bloody journalist looking for trouble.

“When I’m doing my sketches I quite often write down conversations that I’d had and the thoughts and feelings that occur to me. I’ll usually take a few photos as backup to the sketches in case I need to verify detail. Then, when I’m back in the studio, that information is what I use to make the paintings.”

Tricks Of The Light

It is obvious from looking at a selection of Tom’s paintings that he is very interested in the effect of light and the elements on the environment. He has captured many cityscapes at dusk, illuminated by night lights, or simply bathed in the misty haze of an early morning. But such conditions, by their very nature, are forever changing. Tom explains how he does it.

“If you want to paint in a certain light one day you just have to prepare. For example, if you are trying to paint a sunset, or dusk, then you have to get most of the essential ground base of the painting done before the sun sets, then there is about an hour either side of the exact time that you are capturing when you will be able to observe from life. It is a bit like being a sniper: you have to be ready to pounce on the exact moment. You’ve just got to be ready.

“The most important thing to prepare is your mind. My advice is don’t go out the night before, have a nice meal and think about the painting when you go to bed, so everything is in flow. Then, by the time you get to the canvas, you don’t have to dig the energy out, because it is already flowing.

“If you are in the zone, even if the picture doesn’t turn out how you wanted it to, or the sunset isn’t quite the sunset you imagined, then you can respond spontaneously to the change of condition. You have to be prepared to make a few changes.

“In terms of weather conditions, working in a place like Lebanon is much easier than England. You are almost guaranteed that it is going to be sunny for most of the year, although for four months over the winter it is up and down and rains quite a bit.”

At the time of our interview, Tom was working on a new collection of paintings as a means of discovering new techniques.

“I’ve got a bit of time and space at the moment because I had a big exhibition last June in Beirut and probably won’t have another for a couple of years.

“I’ve been focussing too much on precise detail so I’m just trying to be a little bit freer and looser and actually enjoy the texture of the paint. And also concentrate more on the light and the space rather than the surface detail of the architecture.

“I just want to enjoy the process and not be so laboured. I’m painting completely abstract colours and shapes on big canvases, so the pictures are suggestive and primarily about the mood of the place. I suppose they are Rothko-esque. I’m using a palette knife and applying really thick paint. As I work on these pictures, I usually start to see some sort of architecture appearing in the abstract.

“Some I’m doing directly from life. This morning, for example, I painted a view out of my window over the port and sea beyond. There are all sorts of buildings going up so there are cranes everywhere. Then there is the beautiful, majestic blue Mediterranean beyond all of this architectural junk!”

What’s In A Name?

It is the job of critics and gallery owners to write assessments and summaries of artists’ work and the task of scholars to review their careers. But, of course, every artist has a desire to be remembered in a certain way. Tom sums up how he’d like to be remembered.

“Like a lot of painters who work from life have done, I want to capture the spirit of a place at a certain point in time. That is particularly important when working in a place which changes as fast as Beirut does. Hopefully I’ll have captured a few legendary places before they are redeveloped or destroyed.

“On a human level I’d like to be remembered in terms of the way I connect with people, and as an artist who actually cut across a few cultural and political boundaries and got through to the essence of what actually makes us feel human. Also as someone who challenged a few stereotypes, tried to cross bridges and increase understanding between parts of the world that seem to be in opposition.

“Now I’ve worked over here and rediscovered my passion and spirit for art and the way I make art, if I did ever return to live in England or London I might approach it in a new way. And England wouldn’t be such a difficult place to be. It is all about perception and your mood.” TF.