In 1972, The Church Mouse, a children’s story book illustrated and written by Graham Oakley, was published in Great Britain. Its beautifully detailed drawings and humourous storyline immediately proved a hit with both children and parents alike. So much so that Graham went on to produce 11 more hugely popular books in the series, the last of which was published in 2000.

“Publishers just consider me old-fashioned now,” laughs Graham Oakley. “I’m no longer publishable. During the Church Mice times I could publish anything I wanted but now I’m no longer in fashion I have as many problems getting a book published as a beginner. But then again, it doesn’t matter. I’m at the age when I’m past caring. I mean, my career is over – I’ve had my day, really. I merely do it to amuse myself.”

It comes as quite a surprise to hear that Graham’s work is no longer valued by the market, begging the question: are today’s children really so very different to generations past? It’s true that there is something quintessentially English about his Church Mice series of books – something which is evocative of a bygone era. The warm humour and intelligent social satire would not be out of place in an Ealing Studios comedy, while the slapstick chase sequences, usually involving a mouse escaping from some sort of perilous situation, bring to mind Buster Keaton’s wonderfully choreographed film work.

Devil In The Detail

But it is the style, as well as the content, which seems to cause market-fearing publishers a problem. Graham’s pictures are full of carefully drafted detail, whereas the prevailing fashion is to produce ever more in-your-face images to grab the reader’s attention.

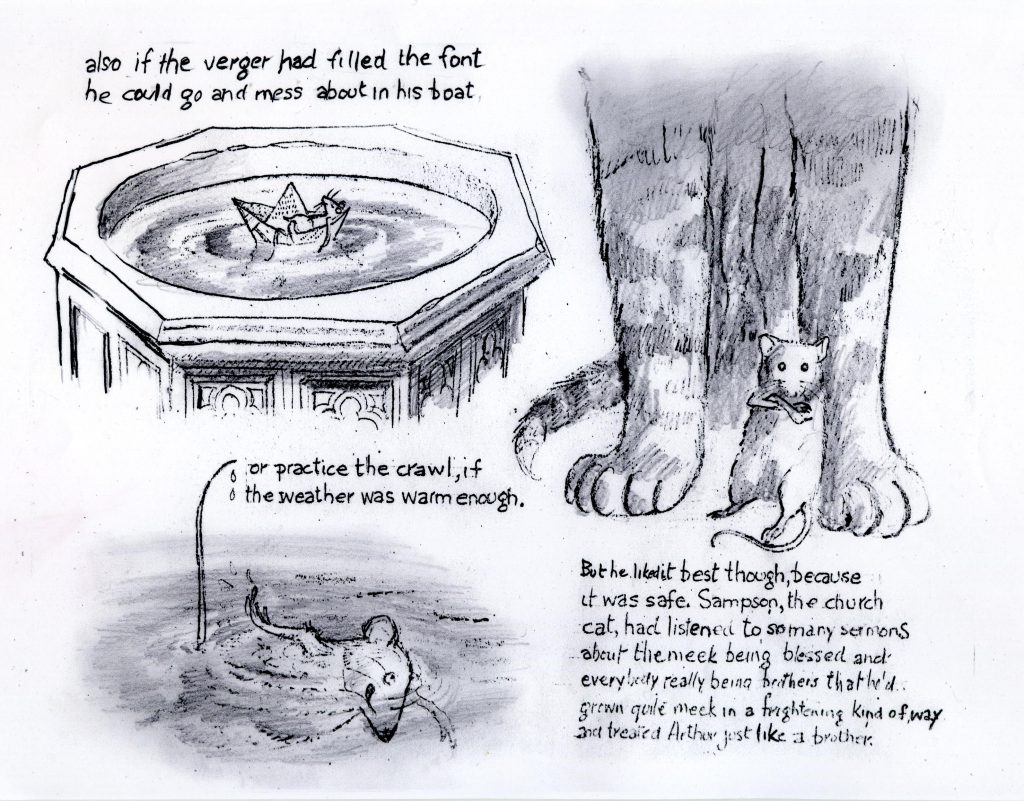

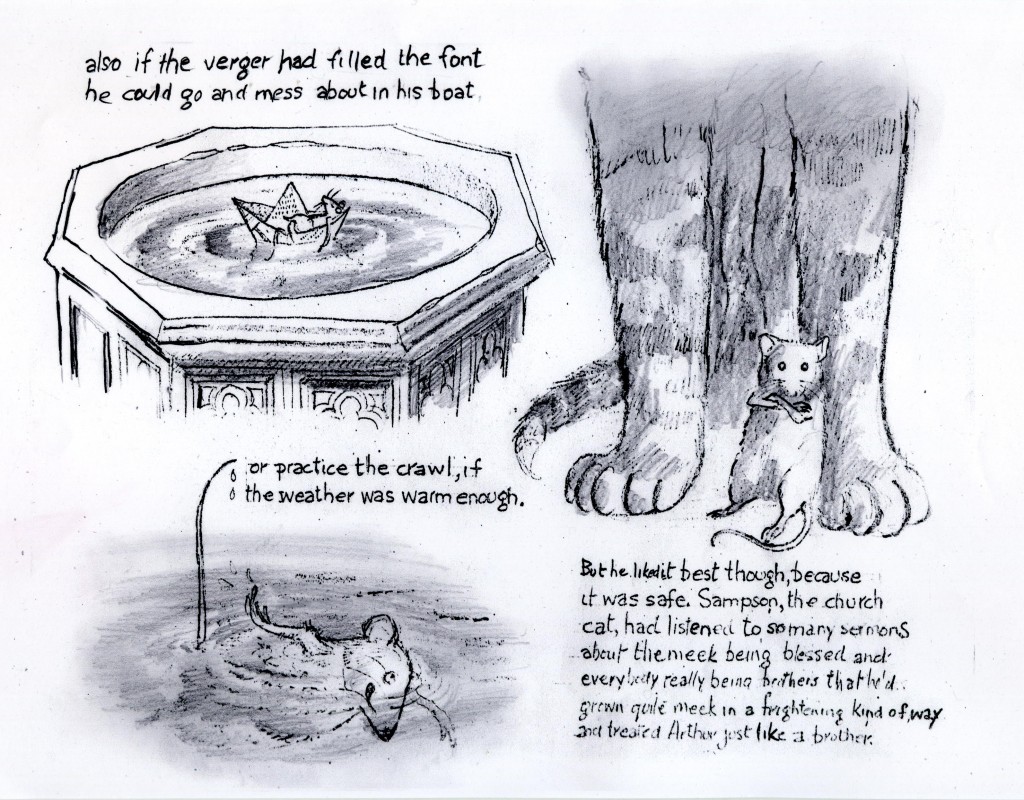

“Certain things come natural to different people,” says Graham on the subject of his style. “I find that I am rather keen on detail, whereas some people like the broad effect. I just feel that broad effects in books are ok but they don’t leave you much to look at after the initial visual impact. My idea was to create books that can be read time and time again. The more detail there is in the pictures, the more things you’re likely to see on a second reading.”

Unfortunately it seems that it is because Graham’s drawings and stories are so well executed that they are now overlooked by publishers. If that is an example of irony, then it is rather appropriate, for Graham’s books are packed full of amusing ironies. In The Church Mice At Bay, for example, a trendy vicar preaching love, peace and understanding creates havoc and fury in the town. In the Church Mice Adrift, houses with ‘welcome’ mats on their doorsteps and names like The Haven and Cosy Nook are guarded by vicious, antisocial dogs and housewives angrily wielding frying pans. Even in the first book, The Church Mouse, there is a toothpaste manufacturer called Wrottam Ltd and a tobacconist store owned by W. Hacker.

“I hope that people find them funny, because that is what I wanted them to be,” explains Graham. But many of the jokes which are hidden in the, often very detailed, drawings are clearly not aimed at children. “I always knew that parents read the books with their children, so I felt that there should be something in it for the adult as well.

“Even my editor used to say ‘Children won’t understand this,’ and when it came to the text my publisher would often say ‘Children won’t know this word.’ But my argument is that if no one ever says it to them they are never going to learn!

“In one book I put the names of the various bell ringing tunes into the text, such as Triple Bob Major, and there were a lot of complaints from the production people who said that kids wouldn’t understand that tunes played on church bells have names. But reading a book is part education. Even if a book is purely for entertainment you can learn something from it.”

Of Mice And Men

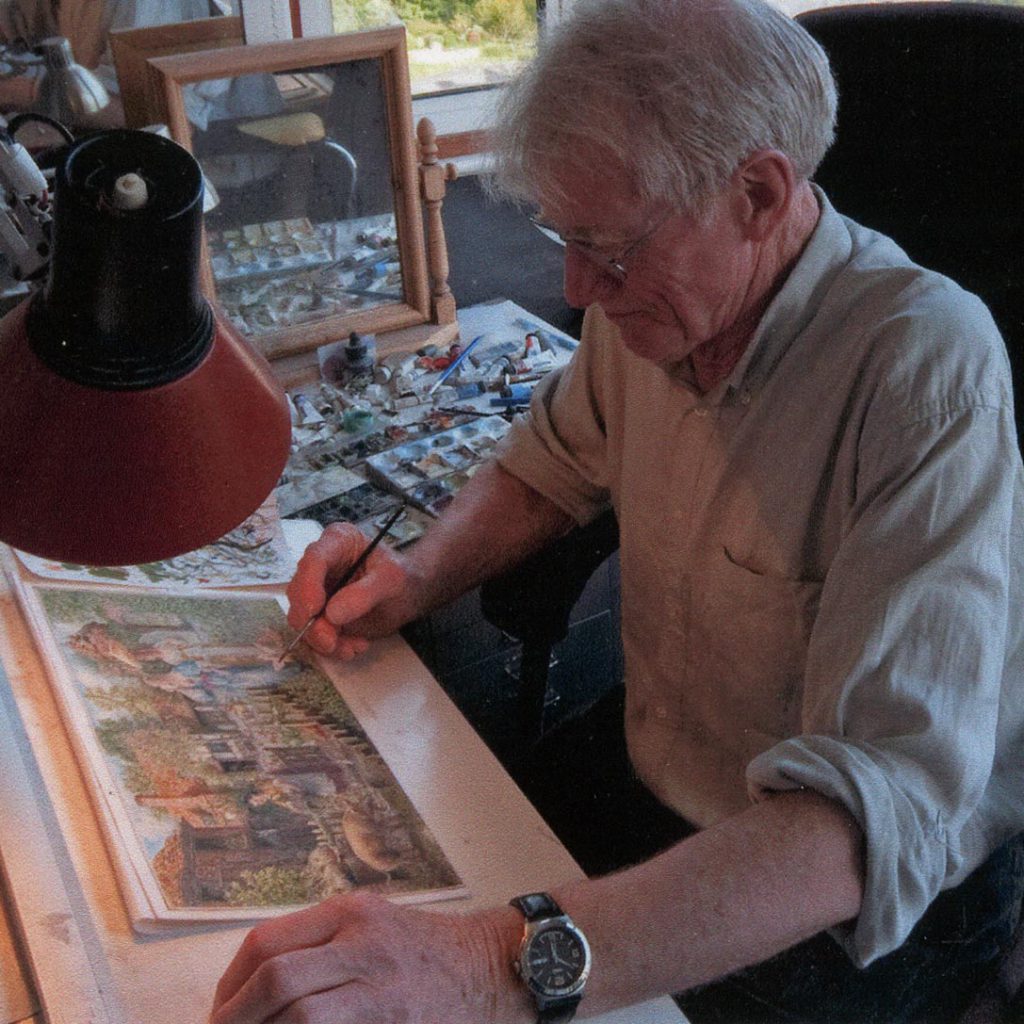

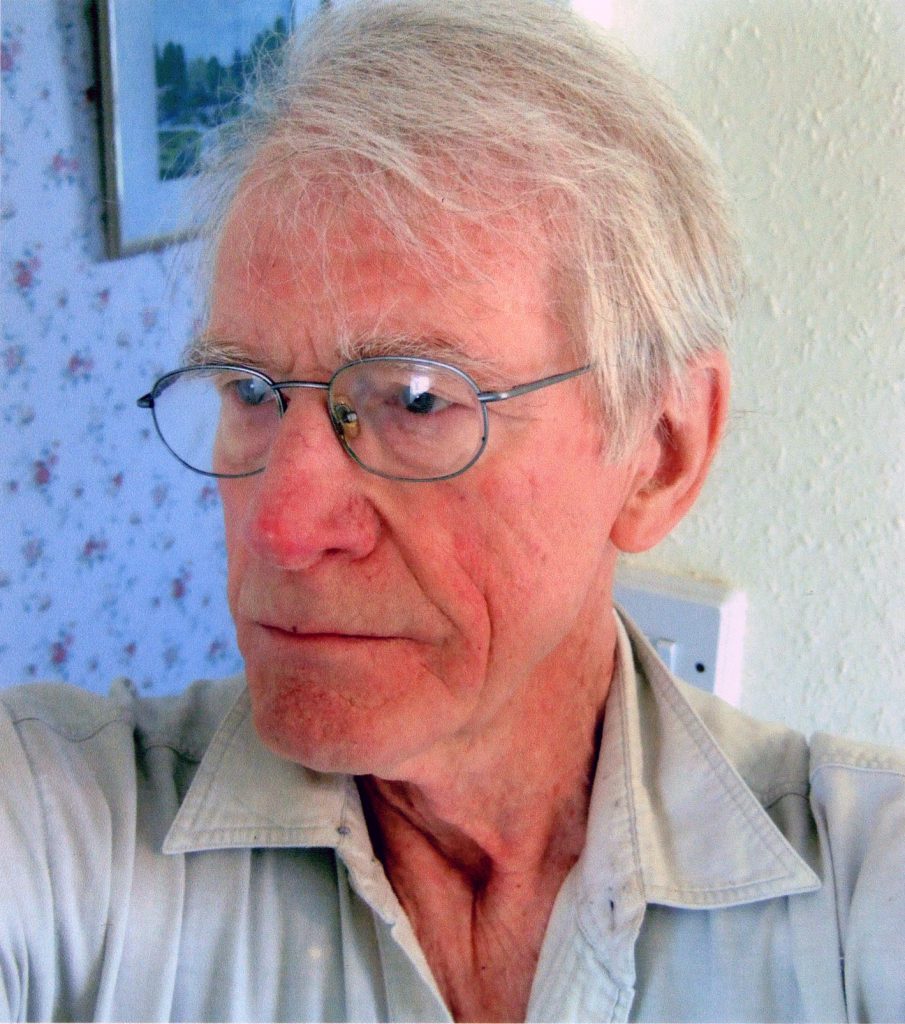

Now 81, Graham was already well into his early forties when The Church Mouse found its way into the shops. Up until that point he had worked his way through an impressive range of art-related jobs which, although not always enjoyable, were formative in his artistic development.

“When I was quite young the prospect of making a living as an artist was almost inconceivable,” insists Graham. “But at grammar school I found that I was good at art and vaguely thought that I could perhaps use it in some way. I was so useless at everything else I had no option in the end! But from my teenage years onwards, it was always my intention to be an artist of some description. Then, when I left grammar school, I went to art school in Warrington and gradually became more and more interested in art.”

One year into his course, in 1947, Graham was called up to do National Service, and was posted overseas to the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) headquarters in Bad Oeynhausen, Germany. When presented with the suggestion that two years of core boot polishing might account for his rather accurate rendering of shiny leather shoes and hobnail boots in the Church Mice books, Graham claims that he’d never thought of it as being a memory of military service.

“I certainly didn’t like it very much! It is something one is glad to forget. The toe cap of the core boot had to look as though it was enamel, which was achieved by using a great deal of spit. I don’t know what qualities spit had, but you had to mix it with the polish then burn it. This had to be done very carefully because if you scorched the leather you’d find yourself on a charge. But if you didn’t do it you would too! Some people took to it very naturally and used to love it. They’d practically spend all night polishing boots. I could never bring myself to do that.”

After National Service, Graham returned to art school to complete his final year. “It was essentially life class, drawing from life, perspective and composition – very generalized. I don’t think they do it like that anymore. Art education is split up into all kinds of subject areas.

“I suppose it was based around what they used to call ‘commercial art’. We did ads for newspapers and that kind of thing. At that time the peak of the profession was, I suppose, to design London Underground posters. That’s what everybody aimed at, but I was always more interested in simple book illustration.”

After art school Graham took a job with a London advertising agency for six months, before an old school friend, who was an actor, persuaded him to study stage design at the Bradford Civic Theatre School.

“I’d always been vaguely interested in stage sets, so I went to drama school and then spent a long time as a scene painter in repertory companies. In rep you design and paint the set yourself. Repertory theatres are pretty few and far between now but nearly every town had one in those days. For each play we used stock scenery and painted it over and over again. There was usually a stage carpenter who would knock up any special bits.

“When I finished with that I went as a production assistant to the Royal Opera House. At the interview it was just a case of showing them my paintings rather than my set-designing skills, but that was also part of what I had to do in the job.

“I started there in 1955 and stayed there until 1957. I was a designer’s assistant so I assisted people like John Piper, who weren’t really stage designers. Piper was doing things which looked almost like his paintings, so we basically turned his paintings into opera or ballet sets. He did The Magic Flute while I was there.

“The job of converting his paintings meant being familiar with the way that stage scenery was built. There would be on-stage things like ground rows, wings that came down the sides and boarders which mask out the lighting. And there were often big constructed set pieces which we usually built on trucks so the scene crew could just wheel them in. Their construction needed us to do detailed, almost architectural, drawings.

“Of course the backdrop could virtually be like Piper’s painting, so the scene painter would just blow them up and they’d end up looking like a large version.

“I stayed there two years then tried my hand at freelance book illustration. I stuck it for a couple of years, but it was hand-to-mouth and just wasn’t working out.”

Changing Places

Eventually Graham gave up the struggle to make ends meet and got a job as a Layout Artist with Crawford’s Advertising Agency, which was one of the biggest names in the business at that time. “The art director would rough out ideas and the layout artist made them look presentable for the client to see,” explains Graham. “I would just indicate the typography that I wanted and a print setter would do it. Now, of course, they do it on the computer in the studio, but in those days the only thing you could use was Letraset transfers. I would order photo prints of things and assemble them to look like the finished job. That was more or less what I did there for a couple of years.”

Although Graham must have gained some useful skills working as a layout artist, he is adamant that the most valuable lesson he learnt was that he hated working in advertising.

“After that I decided I’d prefer to go back to designing scenery and got a job with the BBC television. I went there in about ’62 and stayed for 15 years, eventually becoming a production designer.

“But you start as a temporary assistant, which is really a draftsman working with designers. As an assistant I was mainly working on a drawing board, but then after a time, if you stick it out and pass through the usual civil-service type grades, you eventually get made a designer.

“In that role I was producing the scenery for television shows, including Z Cars and classic BBC serials. The designer would be given the script and then had long discussions with the director about what he had in mind before getting started. We would produce sketches for the director to see and if that was approved, our own assistants would draw up plans for it to be built.”

Graham remembers that at that time the BBC formulated its production budgets using man hours. “You were allocated so many man hours, which you could use in the scenery workshops and paint shops. We also had to select the props. There was, as there still are, dealers who specialized in props and furniture, china and pictures just for films and television. We would compile a designer’s prop list and the production assistants would do an action prop list, which comprised all the things the actors would actually use. But the designer was ultimately responsible for selecting them.”

Of course, at that time, designers could not browse the internet for images and information when doing their research. Instead, the BBC had its own comprehensive book and image library which was available to all departments. “You could use your assistant to do research, who would be sent off to find pictures of 18th century battle ships, or whatever you needed.

“One production would be set in London offices, or in a police station, then a few weeks later you would be on a classic serial doing Georgian interiors or Gothic interiors – you could end up doing just about anything. Sometimes we’d be fabricating the decks of steam ships and filling whole studios with them. You’d be allocated these shows by a design manager who got to know what each designer was best at. So with any luck you would get shows you were interested in. The last show I did in television before I left was a version of Treasure Island in 1976 or ’77.”

Free (lance) At Last!

It was while Graham was at the BBC that he began sketching out ideas for a book which would eventually be called The Church Mouse. Despite the day job, Graham was still finding time to do some freelance illustration work, and had been working on drawings for a McMillan publication titled The Dragon Hoard, when he first showed his rough ideas to the publisher’s art editor. She liked what Graham had done, and so he continued using his spare time to make the finished drawings for The Church Mouse.

When the book was published in 1972, it proved very successful, and Graham found himself adding a new book to his ‘Church Mice’ series almost every year for the rest of the decade.

As soon as the books started bringing in enough money for him to live on, Graham resigned from the BBC. By that time he’d bought a ruined water mill on the river Avon in Wiltshire; one which required a huge effort to renovate. He used the summer months to carry out restoration work and spent the winter ones writing and illustrating the latest book in the series.

“When I started the Church Mice books I was doing them as a relaxation, just as light relief from working in television. But when I left television and began rebuilding the mill, drawing the books was relaxation from the hard physical labour I was doing.

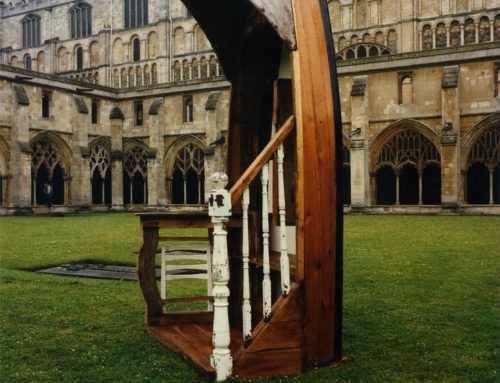

“My initial idea when I did The Church Mouse was for each subsequent book to be set in a different building in the town. After the church, I was going to do one in the library and then another in the school. But The Church Mouse took off and the publisher really wanted to keep it in the church. That suited me because church architecture is much more interesting than you’d find in other buildings.”

Having embarked on a series, Graham had to base each book on a definite theme to distinguish it from the last. This he did by looking around at what was current in the media and finding an issue of interest which he could make something of.

“The first book was the exception because it’s not based on anything,” say Graham. “It was really very simple indeed and I had to start thinking harder about the plot after that. At the time I started the swinging vicar story, there was all this fuss in the media about trendy vicars who were introducing rock bands into Church. They were all into Indian music, yoga and rock music, so I imagined what a trendy vicar would do. And when I did Church Mice and the Moon it was when people were complaining about the extravagances of town councils. I thought that nothing could be more extravagant than wanting to put a mouse on the moon. Another common theme has been the replacement of the vestry roof, which is often mentioned no matter what scheme they get up to.”

As Graham came up with ever more complicated plot lines, his drawings became more complex too.

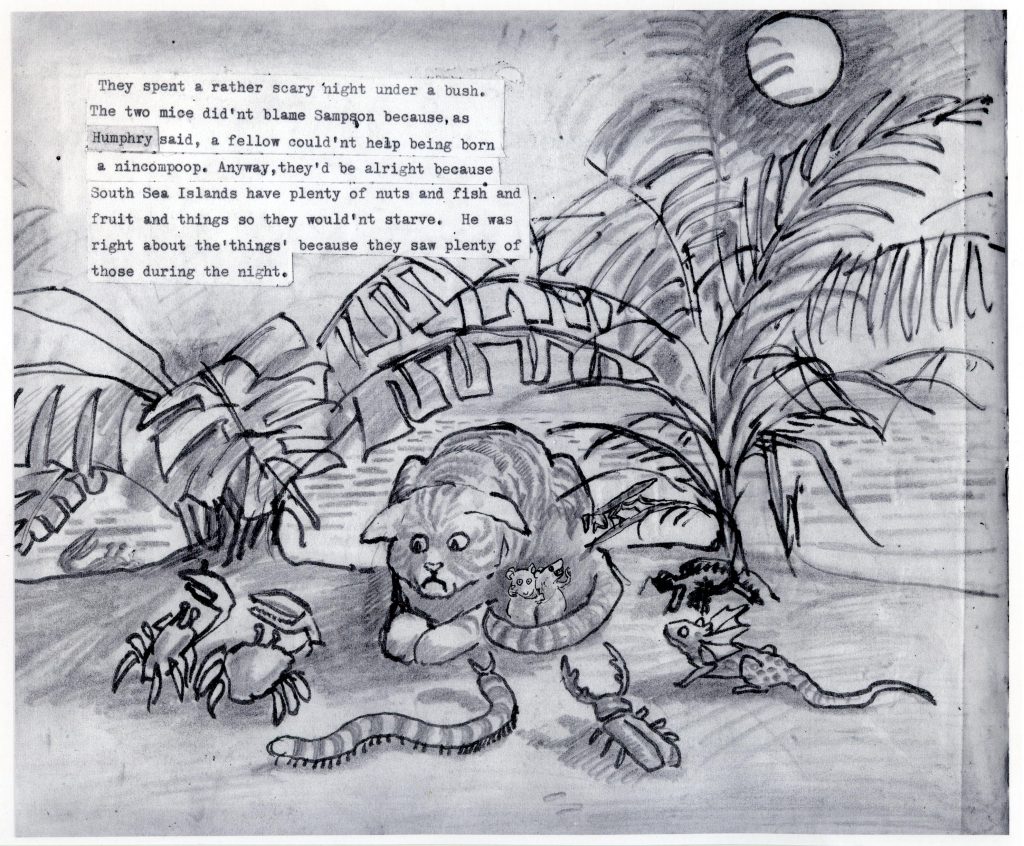

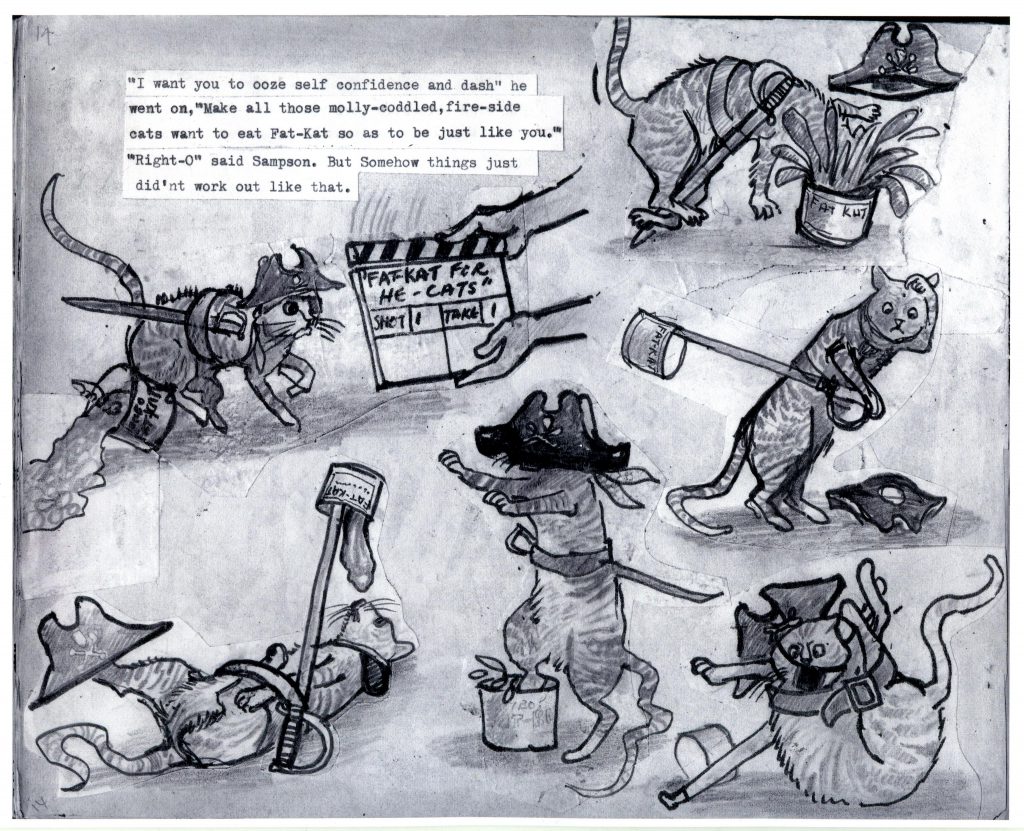

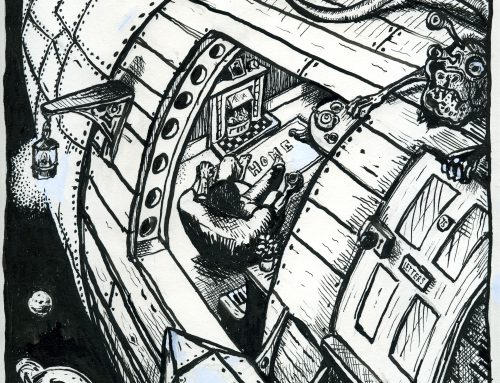

“The second one, The Church Cat Abroad, was based on the theme of advertising and I thought it would be nice to have them get involved in making cat food ads. The plot, which involved them being on board a ship and going to a desert island, meant that the drawings did have to become more complicated. And when it got on to The Church Mice and the Moon, where they actually travel to the moon, I had to start drawing cod scientific stuff.”

Cinematic Influences

Although Graham’s pictures are static by their very nature, they somehow have a cinematic feel to them. Each one tends to show the action from a different angle, as if it were part of a film storyboard designed to help a director position their cameras. And, as mentioned earlier, where there is a chase sequence, what unfolds seems reminiscent of silent movies by the likes of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd.

“I’ve always been a movie fan,” says Graham. “When I was at art school my friends and I were going to the cinema virtually every night. I lived in Warrington, and those were the days when even a small town like Warrington, which wasn’t huge, had 14 cinemas. Most towns were the same. Many of the cinemas changed the program halfway through the week so you couldn’t possibly see all the films that were on, but I made a pretty good job of seeing most of them. And for a long time I wanted to be an art director and work in movies.”

In The Church Mice At Bay, the mice are chased by pest controllers, who end up buried in sand, gassed by their own poison, hoisted into the air by a crane and arrested by a policeman they accidently net. The mice continue into a cat and dog pound which looks very much like a prisoner of war camp. A mighty chase then ensues, eventually involving stray cats, dogs, a naked vicar and the town’s top officials. Graham explains how he thought up such epic set pieces.

“I’m not a great writer or anything like that – writing is something one has to do if you want to do your own books. But the great thing about being a writer-illustrator is that you only write what you think you can draw.

“In that instance, if the cats have escaped from the compound, they need to be pursued, and the obvious thing is that dogs should do the chasing. So you have dogs in the compound too and then you arrange for the dogs to somehow get out of their compound and join in the chase. But when I started the book I didn’t think about that at all; I just came to it. It’s almost like trying to think your way out of a corner you’ve painted yourself into!

“As for the dog pound, a prisoner of war camp does enter into it. It occurred to me as I was drawing that these places are animal prisons. So you then think about all the things that would be in a human prison and adapt it for dogs and cats. So I put in some fortress-like buildings which looked pretty inhuman, and jokes certainly occurred to me at that point.

“As soon as I began writing about dogs I started thinking about Pavlov’s famous dog experiments, so I called the person who keeps the place Pavlov. But you never think of it all in one go. It came to me as it would to anybody suddenly finding they have to think about it.” TF

Graham’s web site is: www.grahamoakley.co.uk

See Part 2 of this interview for more on Graham’s techniques, thoughts and plans.

Part 2 can be found here: Part 2