Over the last 30 years, Stephen Street has worked with some of Britain’s most influential and successful bands and artists. In the 1980s, he was engineer on most of The Smiths albums and produced Strangeways Here We Come, thereby helping to define the classic ‘indie’ sound. When Brit-pop emerged in the 1990s, Stephen was at the forefront again, co-producing Blur’s first two albums before taking the lead on Park Life, The Great Escape and Blur. His other production successes include The Cranberries, Kaiser Chiefs, Babyshambles, Graham Coxon, and, of course, Morrissey.

Stephen Street, Autumn 2011

For many young bands who have grown up listening to the likes of Blur, The Smiths and The Cranberries, Stephen must be number one on their list of producers with whom they’d like to work. Nevertheless, only a lucky few ever get that chance.

“Nine times out of ten there has got to be a vocal on there that I can associate with,” says Stephen, explaining how he goes about deciding which projects to work on. “For me an interesting vocal is one of the key things. There is no point having the best sounding backing track in the world if what you are putting on top is not going to work.

“Sometimes I look for things that are a little bit different to what I have done before to make it interesting for me, but if it is too different to what I do and I don’t think I can associate with it then I know I can’t bring anything to the party. If you do too many things that are in one genre you can get a bit bored and set in your ways, so it is good to do something that’s slightly left-field every now and then. It is all about getting that balance right.

“I’ve always tried to find good things to work on over the years because that is something that helps maintain longevity in the business. I think I have managed to achieve that.

“It is nice to have a great track record and that helps greatly but I get just as excited and nervous working with a new band that hasn’t made a record before as I do going in a studio with a major act. That’s because you are judged on what you are doing with these people and it is their opportunity – it might be their only opportunity – to make a record, especially in this current climate. So I’m very keen to do the best I possibly can for every single act that I work with.”

Stephen working on a mix

The Sound of Street

Of course, when a band or artist is lucky enough work with Stephen, they inevitably want to know how certain classic songs were recorded, and how he achieved particular sounds. As far as Stephen is concerned, however, it is all down to the musician.

“Often I’m working with bands and they ask questions about Johnny Marr and his setup or Graham Coxon and his,” says Stephen. “I always say, especially to guitar players, that the sound comes from their fingers. I can do a song using exactly the same guitar amp and with the same pedals, but whether they then sound like Graham or not is highly debatable, because a guitar responds to how it is played.

“That’s what I love about working with real instruments and guitar bands. It’s not the same as a keyboard plug-in or a synthesizer where the patch is the same no matter what studio you use it in. With guitar players and guitars it can sound so, so different. I’m always in awe of any musician who can squeeze a great sound out of a plank with strings on it!”

Stephen is particularly adept at making very dynamic and un-muddied records, even when dealing with lots of guitar distortion and atmospheric backing tracks which could easily clutter up a mix. Of course, choosing the right equipment and knowing how best to use it is important, but Stephen believes that making clear decisions is also vital.

“We’ve all been in that situation,” insists Stephen, “where you are in the studio and the bass player wants his bass up, then the guitarist wants his guitar up and the then the drummer wants his drums up, and in the end you’ve just got to be able to say ‘No, this is a balancing job and this is the way I see it.’

“I think it is just a question of taste and using your ears, but obviously it is good to have the experience and knowledge of how to EQ and balance things up so they don’t get in the way of each other but still retain some kind of power and edge.

“You can’t please everyone all of the time. I got a lot of flack for making Babyshambles sound too polite, or whatever you want to call it, but I really enjoyed working with Pete Docherty and Babyshambles and making that record with them. There will always be fans who want the record to sound as rough as houses and don’t appreciate the balancing or production job you’ve done on it.”

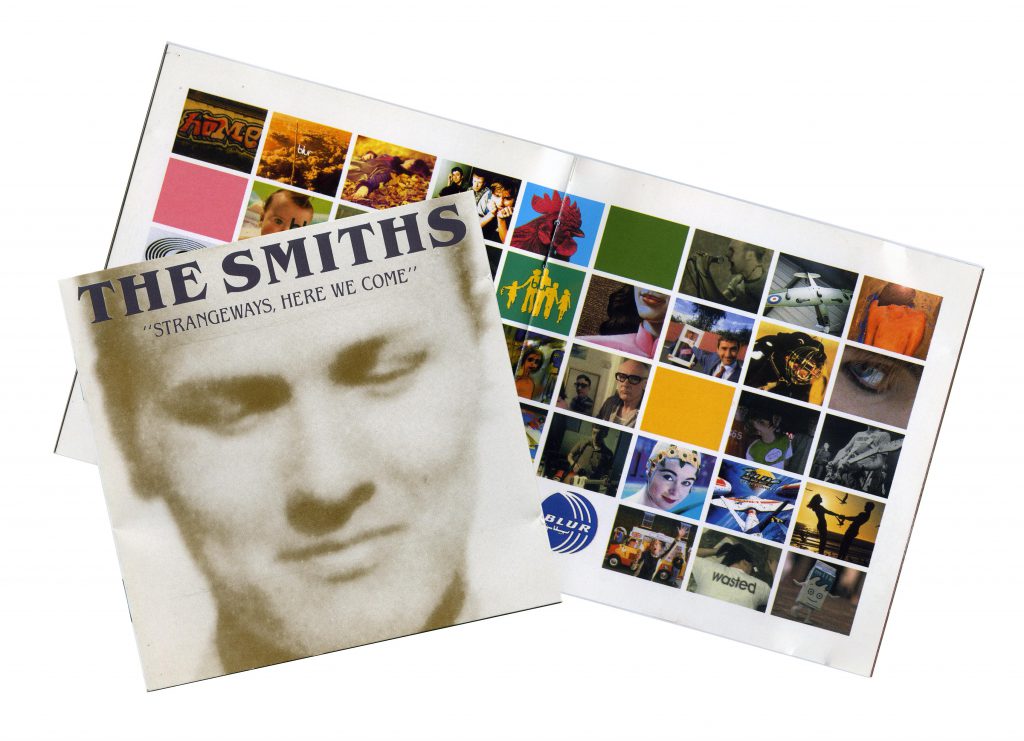

Stephen produced The Smiths and Blur

Working From Demos

These days, when it is possible for bands and artists to work up fairly sophisticated demos at home, Stephen is frequently presented with material which could potentially be used in the final mix. Although scrapping the demo and starting afresh is one way to proceed, Stephen prefers to make use of anything which already shows promise.

“Sometimes a demo has a certain vibe and sound to it and you think, ‘There’s a really interesting sound there and it’s got a vibe of its own.’ When that’s the case why spend ages trying to recreate that all over again? Why not use it?

“I did that on the very first track I ever made with the Kaiser Chiefs, which was ‘I Predict a Riot’. There is noise at the very start, like a guitar pedal being stomped on with a little bit of feedback on it. They’d spent ages getting that right on their demo. So I said to them, ‘That’s a really interesting sound. You are used to hearing that start off the song so let’s use it.’

“If it ain’t broke, don’t try and fix it! That is one of the best laws to remember, and if you can get hold of the demo session and copy that particular thing across then it is worth doing. Sometimes it can be a drum loop that the demo has been done to and it’s just got the right kind of groove for everyone to play along to, so rather than start all over again, I’ll get that loop across and use it as the blueprint. You have to know when to use something and when to say ‘No, actually, that’s taking us down the wrong route; let’s try a completely fresh approach.’

Stephen using his Audient Zen desk to mix a Pro Tools recording

Views on the Industry

When it comes to the music industry as a whole, Stephen is someone who holds very strong views. In the course of his career he has witnessed the closure of many of London’s top recording studios and has watched record sales plummet as more and more people download their music for free. Stephen reveals what he thinks lies at the heart of the problem and what needs to be done if the music industry is to continue.

“The downloading thing has been a major, major problem. I’ve been speaking up for years saying it is not a great idea. You’ve got a lot of journalists thinking it’s a really cool way to get back at the business, but all these people are now realizing that they’ve killed the golden goose and the bands that they have been trying to champion are not getting anywhere because their music isn’t being paid for.

“The reason why bands like Coldplay and Muse are huge is because they made records that meant something and people paid for them. There are new bands out there that really should have got big in the last few years, like Mystery Jets and the The Maccabees, who are struggling to sell a lot of records because too much of their fan base doesn’t buy them. They’ll go along to a gig and jump around in the tent at Reading or Glastonbury, but whether or not they are actually buying records is very debatable. They think, ‘I’ll take the music for nothing because bands make their music from touring.’ Well, they don’t make money from touring unless they are Radiohead or U2 and are selling tickets for huge sums of money.

“It’s all very well for Radiohead to turn around and say ‘We don’t need a record label, we can just give our music away and people can pay what they want,’ but Radiohead had 10 years of EMI investing in them and building them up to the point where they got that position of power. And I think it is really bad of them to have done what they have done. They gave out entirely the wrong message to people.

“The thing about record companies making their money is that they reinvested it into signing new acts. The people who are making money now are the internet service providers who sold broadband on the back of how fast it runs and how great it is for downloading music, but they don’t reinvest any money in music, and nor do the people who run the festivals. The festivals are making a fortune at the moment, shipping bands from one festival to the next every weekend of the summer. But you don’t see those guys going back out there and reinvesting in bands. The only bands that can headline festivals are ones that sold records when records meant something!

“And because of the diminishing sales, record companies don’t want to spend much money on producers. They try and make the records as cheaply as possible, so they’ll send the Pro Tools file to a good mix engineer, like my friend Cenzo Townshend, and say ‘Sort that out.’ Cenzo often moans to me about the standard of the recordings that he has been given to mix and sort out because there have been no production choices made during the process of making the record up to that point. There are just tracks and tracks of Pro Tools.

“The thing that has happened with the arrival of things like GarageBand and Logic Audio is that they allow anyone to be a producer and start putting a few different sounds together. In a way the recording process has been somewhat demystified. You’ve got people all over the country buying microphones, shoving Logic up on their laptops and recording, and with the sounds that are there at their fingertips it makes them feel that they can produce a track. So it has eaten away at the industry as a whole. There are a lot of producers, myself included, who are finding that it is a lot tougher out there now than it was five years ago.

“So I do hope that this current generation of young record buyers get educated to the point where they realize that music is something you can’t just keep taking for free. If you carry on doing that you are killing a great industry. This country has only been second to the United States for creating new musical talent and it is being sold short at the moment.

“I am really hoping that some laws are passed to make it impossible for these pirate sites to set themselves up and willfully share music. Hopefully that will put some worth back into what we do as a job. There has got to be a shift back to people realizing that what we make is worth something. As long as there is some value attached to what we can do then music studios will be able to continue.

“When a studio like Olympic closes it is pretty scary. After Abbey Road, Olympic was arguably the most famous studio in Europe. And it closed because it was creating something that people were taking for nothing. The business can’t operate like that. If Ford Motors were making cars that people took for nothing it would close and this is the problem we have got. Those studios are places where people create something and if we don’t sell it for something it has no value and everyone is going to lose their job and the studios will close.”

View into the small live room from the control room of The Bunker

Money & Celebrity

Most recently, Stephen produced The Subways’ third album, Money & Celebrity, making use of The Bunker to complete the work. The album was notable for being funded using the PledgeMusic system, which enables artist to ask their fans for help financing a project and, at the same time, allows fans to donate money to make it happen. Stephen explains how he became involved in the project.

“The band approached me. We actually share the same management, so at first they were a little bit nervous about asking me, or perhaps my manager was, because it could cause a conflict of interests, but I said ‘Please let me have a listen to what they are up to.’ So Gail, my manager, forwarded the demos that Billy Lunn had done and I was really impressed. I really liked the early Subway stuff where there was that kind of pop punk sensibility to it so I said ‘Yea, I’m definitely up for this, it’s something I feel I can work on and with.’

“Billy is a big fan of what I did with Graham Coxon, both solo and within Blur, and he wanted me to bring different textures to his guitar and make his vocals sound as good as possible. I concentrate a lot on the vocal performances of the artists that I work with so that it’s not all guitars and snare drums. I try and make sure the vocal performances are as good as they can be and lead singers like that sort of input.

“The band wanted it to be powerful and clear at the same time and they also wanted me to make the backing tracks sound tight and rhythmic. So it was a combination of particular desires and it was up to me to bring those to the fore.

Most of Money & Celebrity was recorded at Hugh Padgham’s Sofa Sound studio which, amongst other things, has an amazing collection of microphones. “It’s great to have that,” says Stephen. “I don’t really need that many microphones it in my room because it is such a small space and it is quite an expensive thing to do. Cenzo and I once bought a vintage microphone off of eBay, and it didn’t bloody work, so I am not going to do that again. This thing about vintage microphones being the best is not strictly true.

“We had a very productive session at Sofa Sound and it was pretty quick. We turned the whole tracking around in about four weeks, which is fast these days.

“I mixed in The Engine Room and then I did a couple of remixes in The Bunker. They actually turned out better than a couple I did in The Engine Room, so it was a good challenge to see if I could improve on those mixes.”

Stephen insists that the PledgeMusic method of funding did not particularly affect his way of working, although it did mean that he had to think carefully about studio time in order to keep costs down.

“Obviously it affected the management of the band, getting their budgets sorted out and so on, but not me so much. I just made sure that the studio time that we had wasn’t too expensive and we were quick. So we saved on that side of things. As far as everything else was concerned, that was a decision that was made by the band and their management.”

Saturn 1 mic in the live room with Stephen’s Fender Tele in the background

The Island Way

Although Stephen was still very young when he began engineering for The Smiths, he had already served his apprenticeship, first as a bass player in various ska and pop groups, and then at Island Records as a trainee engineer. At Island he learnt how to produce records using a limited number of tracks and that experience has informed his way of working to this day.

“I still have a bit of an old fashioned approach,” admits Stephen. “I am used to working with 24 tracks and I still like to limit things to a manageable number of tracks. I’m not into mammoth track-upon-track sessions, because I think sound wise it ends up getting smaller. There’s a discipline involved, I think.

“Island had a 24-track Studer A80, which was a great machine. One of the first jobs I had was to learn how to line that thing up. It’s something I don’t have to worry about these days! But one of the key things I remember was when someone brought in an 8-track head block so that the studio could do a tape transfer of some old Free stuff, and it was amazing. The drums were on two tracks, the vocals on one; there was a tambourine and lead guitar solo sharing another track and the bass and guitars were on the others, and it all sounded absolutely massive. It was incredible. So it just shows what can be done.

“Before I joined Island I was a bass player in a band so I was used to being on the other side of the glass, but I saw these great engineering producers like Martin Rushent, Martin Hannett, Steve Lillywhite and John Leckie – all these guys who were producing all this post-punk stuff that was really interesting to work on – and I thought, ‘This is what I want to do. I’ve got some musical knowledge but what I really need to do is learn to use the recording desk as a tool.’ I was very fortunate and managed to get a place at Island as a trainee engineer. And, of course, the quality of the stuff I was working on at Island was always very, very good, so it was a great training ground, without a doubt.

“When I first worked there I was an assistant to a couple of engineers who were working on a lot of reggae and African stuff which was very interesting. Back in the early ’80s, there were a lot of white funk bands, like Haircut 100 and ABC, and there was a big dance scene within the post-punk music. You had Gang of Four with great funky bass lines, so it was good to be involved in that stuff and I saw a parallel between modern punk music and what they were doing.

“There was a great cross-cultural thing going on. One of the sessions I worked on at Island was an album made by the Edge working with Jah Wobble, who was the bass player from PIL, and that was an amazing record to be involved with. So it was very interesting stuff.

“The guys were very good at letting me get my hands on the desk very soon so I wasn’t just making tea forever. I was actually being involved in the creative side of recording and mixing which is why it was a great training ground. And then, like everyone in the business, I got a very lucky break when I teamed up with The Smiths when they came in to record ‘Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now’. That was the start of my association with them.” TF

Taking a moment off for a photograph

Part 2 of our interview with Stephen can be found here: Part 2