Steinway & Sons are one of the most highly-respected piano manufacturers in the world, and Abbey Road is arguably the most famous of all recording studios. Haydn Bendall has worked for them both. He talks about his experiences in the industry.

“I don’t actually think the engineer or producer is that important!” says Haydn Bendall and laughs. “There are Kate Bush albums which contain some tracks I’ve recorded together with tracks recorded by different engineers, but when I listen to those albums now, even I can’t remember which songs are which, because they don’t sound like the work of two different people – they sound like one artist with one group of songs, and they sound fine whoever did them. Some albums I’ve worked on haven’t sold at all, whereas others have been huge successes, yet I’ve recorded things more or less the same way for the last 20 years, and with the same attitude. So I’ve concluded that if an album turns out to be great it is nothing to do with me, I was just lucky enough to be there!”

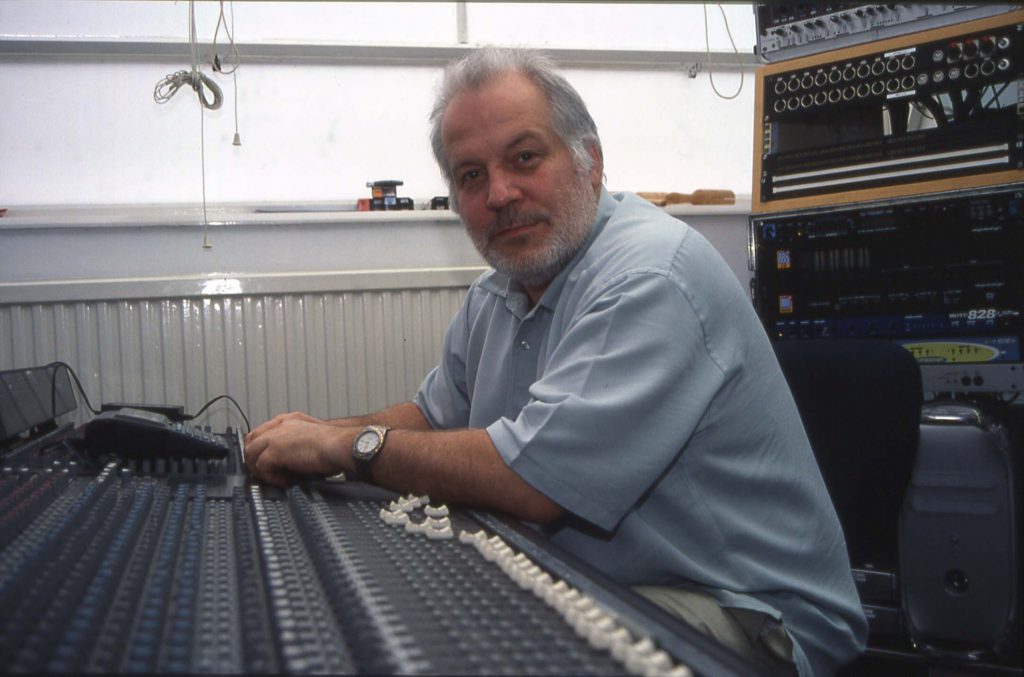

Luck may be partly responsible for Haydn’s presence at certain classic recording sessions, but it wasn’t just luck that secured him his engineering post at Abbey Road studios, and kept him there for 17 years, and it takes more than a bit of good fortune to become an employee of a highly regarded piano manufacturer like Steinway & Sons. Quite apart from having to have some level of basic talent in the first place, doors in the industry only swing open for those who display huge amounts of enthusiasm, dedication, persistence and endurance. Over the years, Haydn has demonstrated all of those qualities, and his obvious interest in people, and his love of the social aspects of working in a team, must have greatly helped him too.

Starting Out

Music has always featured strongly in Haydn’s life; from his childhood, he remembers his parents listening to Tchaikovsky, Beethoven and Brahms, and more contemporary artist like Ella Fitzgerald, Danny Kaye and Tommy Steel. The family also had an upright piano which proved to be a fascination for Haydn. “I was transfixed,” he says, “I just thought it was an amazing instrument. I used to sit with my ear right against it.”

But it wasn’t until Haydn’s teenage years that music really became important to him. “Around that time the scene changed so that by the early sixties there was this music that was purely for our generation, and I became really passionate about it. From working in an ironmongery shop and doing a paper round, I managed to save up enough money to buy a Vox Continental organ, and then a Vox AC30 amp to go with it. I joined bands at school and we used to play round local youth clubs and pubs in the East End of London and Essex.”

Nevertheless, when Haydn first thought about pursuing a career, medicine and teaching were on his list, and when he decided to do an Open University degree, while working for Steinway & Sons, he chose sociology. Strangely, music never figured in Haydn’s plans. “It never occurred to me that I could earn my living doing music,” he admits, “It just seemed to be something other people did. I was just enjoying myself, and in those days nobody was worried about getting jobs or housing – there were loads of jobs. The only thing most of us worried about was Vietnam, the possibility of nuclear war and the stability of our home lives. The rest of it was really easy!

“But while I was waiting to go to York University our band started doing some recording with our manager Cliff Cooper, who owned a little recording studio in Stratford. There was only room for the organ and guitar, and we had to put the organ on top of Cliff’s Mellotron and stand on a chair to play, but I really enjoyed the experience. Cliff was quite a business man, and he soon started a company called Orange in New Compton Street. They made the famous Orange amps. Downstairs he built a new recording studio with a state-of-the-art Ampex four-track tape recorder. I needed a job before I went to university so I started working there as a tape op. As soon as I got into that recording studio it was like someone had clicked on a light.

“I met and played with some fantastic people there like Robin Gibb and the Greek band Aphrodite’s Child with Vangelis and Demis Roussos. The experience was beyond my wildest dreams, and it was then that it hit me that maybe this could be a way to make a living. I loved the way you could change sounds or the direction of performances, and it was both thrilling and fascinating to me. So I stayed at the studio for two years and didn’t go to university.

” I didn’t really take much of the technical stuff in at the time, but what has stayed with me is the sense of fascination. In most areas of my life I feel quite clumsy and inarticulate, but as soon as I walk into a studio I feel totally at ease and I feel a sense of absolute quiet.”

Going the Stein Way

By his own admission, Haydn worked himself to exhaustion at Orange, and eventually had take time out at home to recover. The studio experience had been invaluable, but Haydn needed to do something different for a while. It was then that his fascination with pianos offered him a new direction. Haydn takes up the story. “I got talking to the piano tuner who was working on my parents upright and he suggested I consider becoming a piano tuner. He explained to me that he got to travel all over the world with just his bag of tools and he was always meeting really interesting people who loved their instruments. He made it sound very attractive. I liked the idea of being a mercurial character travelling around, and I loved pianos, so I got myself an interview at Steinway & Sons, and they subsequently gave me an 18 month apprenticeship at their workshop in Park Royal.”

The Park Royal workshop was where Steinway sent their pianos for repair, so the in-house apprentice scheme allowed students to learn first-hand about piano construction, repair techniques, and toning issues, as well as basic tuning skills. Haydn explains why such a breadth of knowledge was necessary. “When you are working in concert halls or recording studios you have to be able to fix anything which breaks or isn’t working properly. A string or hammer may break, or a certain note might start sticking, or may be sounding too bright. You have to know what to do because there may well be an orchestra waiting for you to fix it.

“You can adjust all sorts of things. For example, it’s possible to re-shape the piano hammers to get different sounds. To do that, you have to bring the whole keyboard action out of the piano onto your lap so that you can get to the hammers. Each hammer is covered in compressed wool, and it is the wool part which hits the strings. By modifying the shape and texture of the wool, different tones can be achieved. We used to use a thick stick with sand paper gummed onto either side to reshape the wool of the hammers so that they had either sharper, or slightly more rounded ends.

“We also had what we called a toning tool, which was basically a wooden handle with a little brass fitting at the end which could hold three sewing needles. You fit the needles into this contraption, and then stab them into wool of the hammer. The action slightly separates the wool fibres, making the hammer less hard, and giving you a softer tone. It’s actually quite a skilful process, and not something you’d do haphazardly.

“I was at Steinway for four or five years and it was a great experience. I found myself working at many London town halls and studios, and, for the first time ever, I heard orchestras being recorded. I was a bit older and wiser than I had been in the Orange days, so I tried to take it all in. I also met some amazing talents like Rubenstein, Ashkenazi and Alfred Brendel.

“Those players knew their instrument intimately, and were sensitive to every nuance of every note. They may not have totally understood the techniques required to repair pianos, but they were very analytical about what was right or wrong with the keys. If a note was bright, sharp, didn’t sing for long enough, or if it sounded hollow, they would be able to tell, and would want it adjusted. I would have to try and mould wayward notes back in with the rest. The tuning aspect of the job is the matter-of-fact part so it’s actually relatively easy, whereas everything else is a matter of opinion.”

While working for Steinway & Sons, Haydn found himself tending to the pianos at many Abbey Road Studios recording sessions. During those times he became friends with studio manager Ken Townsend and his deputy Mike Gray, and eventually informed them both that he really fancied working in the studio as an engineer. No full-time vacancies were available at the time, but Haydn was offered a part-time job which required him to work weekends and nights. “For about a year I helped set up sessions, and I worked a lot with tapes, which I’d done at Orange, so I was confident about dropping in,” says Haydn. Eventually one of the full-time engineers decided leave, and Haydn was offered the job, subject to a three month probation period of employment. Three months passed without a word from anyone, so Haydn assumed that all was well, and the job was his. He stayed at Abbey Road for the next 17 years, spending 10 of those as senior engineer.

Back Down the Road

Haydn has very fond memories of his time at Abbey Road, which spanned in the years from April 1973 to 1991. During that time he had the privilege of working with a huge number and variety of artists, musicians, and producers, and he learnt how to engineer the Abbey Road way. Haydn recalls how the studio was structured in the early ‘70s. “When I started, there were about 80 members of staff. There must have been about eight engineers, and the rest were tape ops, administration staff, disc cutters, catering people, cleaners and porters – it was big. Even though I loved the place, it was extremely insular because no outside engineers were allowed to work there, and Abbey Road engineers weren’t allowed to work anywhere else unless it was for Abbey Road. I don’t think I was ever given a contract of employment, so it was just one of those unwritten rules. Also when I first went there 80 percent of the work done there was for EMI.”

Being so insular, Abbey Road nurtured a working methodology which went beyond recording techniques to encompass every aspect of studio practice. Haydn describes how the recording and technical engineers would prepare and conduct a recording session. “Some time before a session, a decision would be made to record at either 15 or 30ips, with or without Dolby, at a certain level, and a particular brand of tape would be selected. You’d make those decisions based on the sorts of sounds you wanted. If it was going to be a hard rock sort of thing then you’d probably choose Ampex tape. If it was going to be a slightly softer sound, then a BASF or 3M tape would be a better choice. If you didn’t want to load the tape too much and therefore get tape compression, then using Dolby would be strongly considered.

“You’d also make sure the whole album was done using the same batch of tapes, so hopefully they’d all share the same record characteristics. Just like a photographer uses certain films, we got to know the characteristics of the medium.

“The technical engineers would line up the tape machine to suit the engineer or producer’s requirements. They’d use a reference tape to make sure that a whole set of frequencies played back at the correct level, and that that the replay of the machine was as flat as it could be. They’d also check the record side of the machine, by playing certain tones from the mixer at a particular level, and make sure the machine recorded those correctly. The whole process was done before every session, or at least at the start of every day.

“Then you’d start recording. As soon as you had a master backing track the tape would be cut and a couple of minutes’ worth of two-inch wide white tape would be attached at the beginning of the song and some red tape would be added to designate the end of a song.

“There were very strict rules about how tape boxes were labelled. We had to keep copious notes about everything we were doing. We’d make careful notes on the tape box indicating where the song started and ended, and where all the parts were situated. The track sheets would say what was on each track and where, and they would be kept together with the tapes. Tapes were always put away and store tail out. The absolute preciousness of the master tape, or any tape for that matter, was of paramount importance, and that absolute care is an Abbey Road trait.

“Having worked like that for so long, it really pisses me off when I see people working on a track in Pro Tools in which they have bits of mysterious unlabelled audio floating around. That kind of disregard for audio drives me mad! With all the tracks you have today it is even more important to know what is going on.

“At Abbey Road, we were taught to always assume that tomorrow somebody else might be working on the track. Most of the time you would be seeing a project through to the end, but there’s always a chance that you might be ill, or unavailable for some reason, and so a project had to be documented so that a different engineer could walk in and take over seamlessly.”

As well as having to adhere to strict procedure, the Abbey Road staff were expected to conduct themselves in a fitting manor. “Everyone had to be incredibly professional, so a tape op would give the engineer and producer absolute respect. If you were doing something in the studio then that was the most important thing in your life at that moment. Nothing interfered with that, so you definitely wouldn’t be taking any phone calls. You would try to make sure everything went well.”

Despite the strict doctrine, engineers were still allowed to develop their own working practices. “The equipment was always the engineer’s choice,” explains Haydn. “After a while you got to know each engineer’s setups, so much so that you could do their setups for them. For example, you’d know what mics a particular engineer liked on the drums. Personally, I use between 12 and 16 mics on a kit, although they normally gets condensed to five or six tracks. I like using mainly dynamic mics on drums. I tend to use B&K mics for overheads, and Neumann 87s or M50s for ambience. Every now and then I try a new idea but if it is in a room I know, with people I know, I tend to keep pretty much the same setup. I probably haven’t radically changed the way I record drums for the last 15 years.”

Many of the recording techniques Haydn learnt and developed at Abbey Road have stayed with him to this day. He is quite particular in the way he uses a mixing desk, for example, preferring to record and monitor with his faders in a straight line. “When I’m recording I sort out the panning, and set my monitor fader levels to about -5dB and the record faders to 0dB. Then I adjust the balance with the mic inputs until the mix sounds about right. Having the monitor levels at -5 provides a nice bit of leeway for moving something up or bringing it down. You have to take into account that you will be using positive and negative EQ which will change the levels a little.

“Using this recording method basically gives you the best signal-to-noise ratio of the mixer. For example, if you try mixing when the faders are at -20, it’s impossible because the slightest fader movement is a move of 5db, but if you have monitors up at minus five you can make adjustments of half a dB quite easily. Lots of people will argue, with good reason, that by doing this you are not loading tape as fully as you could, so you are not making the best of its signal-to-noise ratio, but I feel much happier working this way because I can put up a mix very quickly. Once the pans are right and the faders are in a straight line I have my basic backing track working. That applies to the echo sends and everything else. It means that when you are working on an album you can return to a song and not have to mess around getting a monitor mix. It makes mixing a lot easier, more efficient, and somehow more musical and dynamic. I’m comfortable doing it that way because I always know where I am.”

Tools of The Trade

Despite having used some great studio equipment over the years, Haydn views the gear in the same way he does the role of the engineer or producer – as not being particularly important. “There are certain pieces of equipment that I love and I am pretty careful about the microphones I use, but over the years, I’ve become more interested in the passion and the musicality of recordings than the technicality. That is what people are buying. Much as I like to use good equipment like Avalon mic amps, people don’t buy records because you recorded the voice on one. Obviously, if you have a really great performance, it makes you want to record it the best way you can, so you will end up using the Avalon mic amps and a Neve VR desks, and they become very important to you. But, for example, much as I love Abbey Road, it owes a lot of its fame to the Beatles who were only there because EMI sent their artists there, but their music would have sounded fantastic wherever it was recorded.”

“Like everybody else, I use Pro Tools for editing but, for me, working on the computer is nothing more and nothing less than word processing, so it doesn’t excite me. I used to really like Opcode Studio Vision and I’ve spent long periods of time doing sequencing and programming for clients so if somebody says, ‘look, I’ve just programmed such and such,’ I usually think, ‘that’s great, but I could do that’, and I’m never particularly impressed by things that I can do myself! However, if somebody plays something or sings something, it always impresses me. There are certain artists I love, and it doesn’t matter if they are using a guitar, keyboard, piano or loop, because the artist and music are much more important to me than the methods used. But I become suspicious if the method becomes more important than the music. And I suspect that is sometimes the case.

“Programming is a very lonely pursuit, and I love being with people and musicians, and being part of a team.”

Moving On

After leaving Abbey Road in 1991, Haydn became a freelance engineer, and continued expanding his musical interests. Today he’s involved in several business ventures based at The Firebird Suite studio complex in Wembley, North London. The Firebird Suite is a facilities company which also offers post production and voiceover services. Under this same roof is a production company called Schtum through which Haydn put a lot of his work. Between them, the companies handle everything from recording to remixing and re-mastering, and cater for DVD, SACD and CD formats.

A third business, which Haydn and several other colleagues will be starting together in the very near future, is a record company. It too will have a base at the Firebird Suite. Haydn is particularly enthusiastic about the project. “I honestly believe there is a really good future for small labels at the moment. If you sell half a million albums then fantastic, but you can earn a good living from releasing four or five albums a year which sell 40 or 50 thousand copies each. I’d like to see a label develop as a real identity and character like ECM in Germany. They have a reputation that almost outstrips their artists.

“I want to start this label because I get passionate about certain music and I am being drawn towards unusual projects more and more. The label would also give me a vehicle to work in the studio. I don’t want to wait around for months only for a record company to change its mind. I’m not interested in long contracts, well just sign artists on a one album deal so if they want to do other things they can. The important thing for me is working with people who are enthusiastic and enjoying what they are doing.”

“You only have so much room in the mix, so if a guitar is going to sound big and loud then there will be less room for the keyboards, drums, voice and bass. If I am trying to get a balance for a complicated mix, I approach situations like I would and orchestra. Each element is playing its part to make up the whole sound spectrum, so I am very careful about panning, and careful about EQ and balance.

“I find that you can have a mix which isn’t working, but moving one fader a little bit up or down makes the whole thing suddenly lock into place. That tends to be a balance thing more than anything else.

“The most difficult part of mixing is finding the centrepiece of a track. By centrepiece, I don’t mean anything specific like the drums, guitar or bass, I’m talking about the thing which is transferring the song’s energy. So I usually spend quite a lot of time getting a balance right before putting it anywhere near a computer for editing.

“During this balancing period I quite gently EQ certain things, so the EQ and the sort of reverbs and effects I want to use are more or less fixed. I’ll keep all that, but then I’ll pull all the faders down and rebalance. Sometimes I’ll pull the faders down three or four times during the course of a mix. I find that it clears away anything that I was holding onto dearly. It’s like having a nice shower. You’ve done all the preparatory work, so when you start again you’re just worrying about balance.

“You’ve got to be quite brave, but also quite honest, and if something isn’t sounding very good, even though it sounded good during recording, and all the elements are there to make it sound good, you know that the only reason it’s not working is because of you. So you have to pull down and start rebalancing. Once you get the core of the track right, the rest of it comes together in minutes.”

“I’ve been guilty of mixing the life out of things in the past so I try to get everything in pretty quick so that the EQs, reverbs and other effects are working, and then I go through that rebalancing process. A mix is never really finished, it’s just abandoned, hopefully at the right time. Sometimes it’s necessary to stop because of the budget. When I was at Abbey Road, I didn’t even know what the budget was, so if we needed an extra orchestra here or there it would be fine. But there is not so much money available for recording these days so now you know more about the budget than you do about the music.”

Post Script: Leaving the Abbey

“One of the reasons I left Abbey Road was because Ken Townsend was going to leave and I really wanted to go while he was still studio manager. I had, and have, the utmost respect for him as a human being and as a studio boss. Perhaps he wasn’t the most efficient person in the world, but without a doubt he was a great studio boss. He understood studios, musicians, engineers, finances, technicalities, and he considered everything in a very humane and humanistic way.

“I was unhappy with the place becoming very corporate and being run by accountants, and I don’t think that is the right way to run the studio. The engineers were, and still are, on a very good salary so I could see that many people would be made redundant, and I didn’t want to be one of them. I was eventually proved to be correct because some very loyal and highly-valued members of staff were made redundant, for whatever reason.

“I don’t miss the place as it is now, but it is still a fantastic place to work, technically it’s second to none and the equipment is fantastic. They have a wonderful collection of mics, some of which are very new and some very old. They don’t slavishly follow the trends for new bits of gear, instead, they buy equipment depending on what it sounds like. They have followed the fashions for Neve and SSL desks, but they are fantastic desks.” TF.