What one person thinks of as rubbish is not necessarily without value to others. Artist Thomas Flint explains why he uses found objects to make sculpture, and how he goes about turning other people’s junk into art.

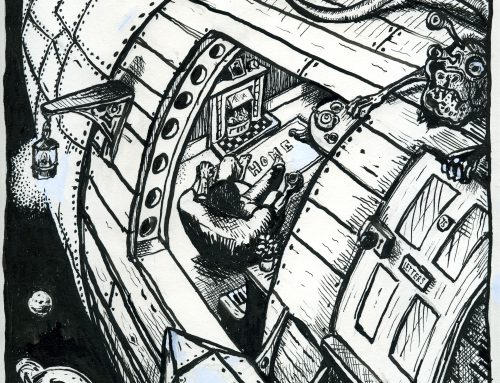

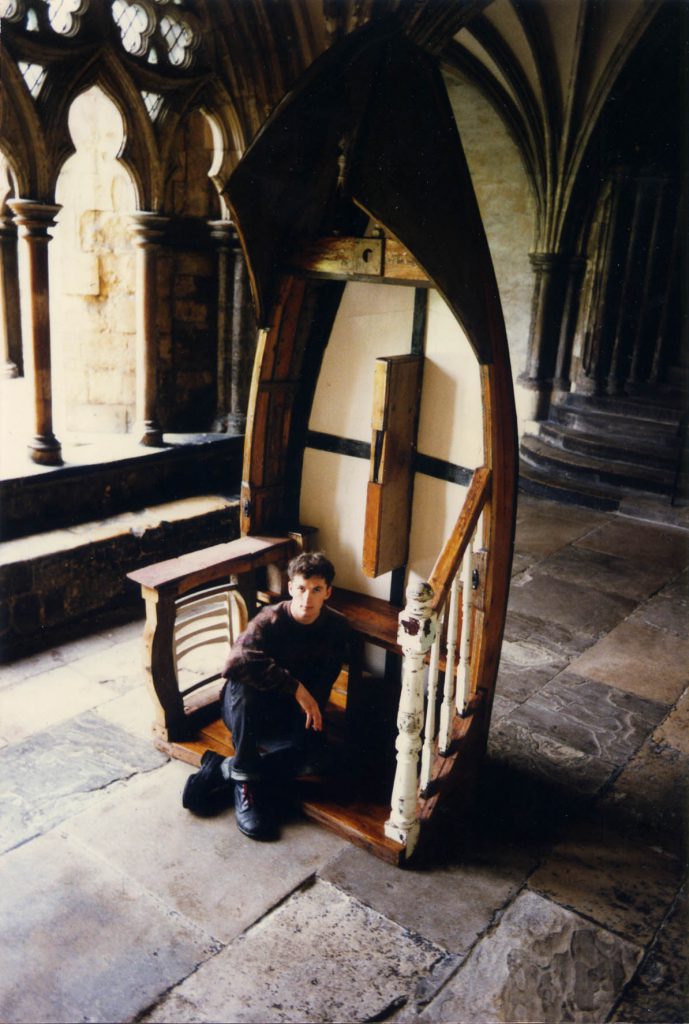

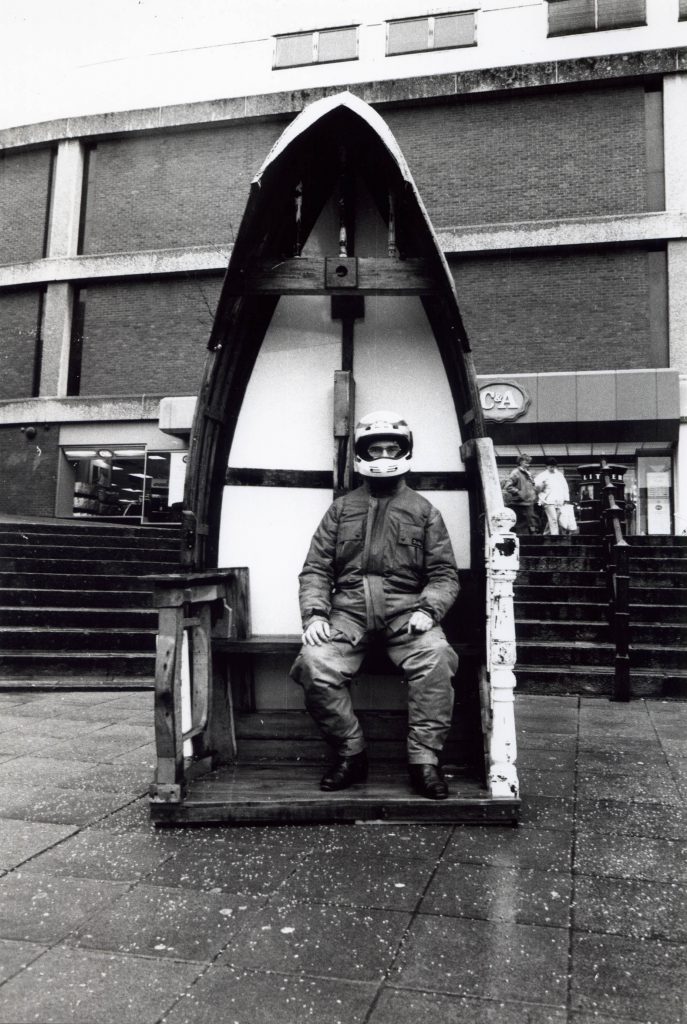

Thomas and his Boat sculpture, in the cathedral cloister

My approach to sculpture is not a traditional one. If I was making public art, I suppose I would have to turn to materials like stone or bronze, but if the work is intended to be seen inside then anything is fair game in my book. I actually use cardboard quite a bit, which clearly isn’t suited to outdoor installations, but has some really interesting properties. It’s surprisingly strong, very light, easy to cut, glue and manipulate, and has a texture and warmth that I like.

But I don’t restrict myself to a particular material or anything as definite as figurative or abstract work – it can be anything, as long as the idea is good. I trade in ideas, primarily, but they have to be engaging. Ultimately, all art is entertainment of a sort, so whether there is a deep message behind a piece, or it is just some frivolous notion, it has to be of interest to people.

American Pie. Thomas: “The cardboard frame was covered in flyers and adverts for products, and the painting was done so that these showed through.”

Getting Started

While I was at school I excelled at drawing and painting and was, I remember, generally perceived as being the best at it in my year. Although this was a great confidence booster (I wasn’t great academically), I was unable to identify a direct use for my fine art skills and saw my future as being in design. I was also very good at CDT (Craft Design and Technology) and found that the design process I was being taught had a logic and purpose to it which I found to be lacking in painting. Industrial design was probably where I was headed at that point, or would have been if anyone had told me it existed, but the foundation course I took after A-Levels closed down my options rather than open them up, as I’d hoped it would, and with some uncertainly I found myself applying to study sculpture.

The course I eventually got onto included casting, welding, woodwork and stonework and there were also opportunities to venture into other departments, such as photography, printmaking and painting, so it was good for picking up a wide range of practical skills.

It wasn’t quite the design course I’d originally had in mind, but it was the closest thing I could find at the time that, for me, ticked certain boxes.

I quickly found that sculpture presented me with certain challenges which painting did not. In a painting, anything is possible, for it is only a 2D illusion. A sculpture, even if it is pretending to be something it is not, still has to abide by the laws of gravity, and therefore has a structure which is related to its appearance. Dealing with structural integrity was enough of a thing for me to get my teeth into while I looked at how I could use sculpture to express my ideas and satisfy my creative drive.

One particular concern of mine was the environment. Although I wasn’t interested in campaigning, it seemed crazy to me that things were made just to be thrown away. I have a love of old things – buildings, ruins, mature trees, household objects, furniture, books – which have a history and character, and I have always hated seeing such things tossed into skips (in the case of objects and materials), and pulled down (in the case of buildings and ruins). This concern, coupled with a lack of cash with which to buy new materials, soon had me pulling objects out of skips and using them to make sculpture.

At about the same time I also experienced something of a revelation, which was that nothing I could ever make or draw from my imagination, would come close to the designs of nature, which are the result of millions of years of evolutionary experimentation.

I looked at plants and thought, ‘There is no point painting that, it already is everything it needs to be.’ Nature has dealt with issues of structure, colour, texture, pattern, purpose and environment pretty thoroughly. I knew I had to make something different.

Similarly, when I started thinking about manufactured objects I noticed that they are often very beautiful in their own way, but realized that this beauty is not something contrived simply for aesthetic reasons. For example, the look of an object is usually a reflection of its function, and the materials used to make it will be appropriate for the job it is designed to do. There are other factors at play too, such as economics and the limitations of industrial manufacturing. I felt that nothing I could dream up would have the integrity of a found object, made to satisfy a multitude of demands.

What I realized I could do, however, was select objects and re-use them for my own purposes, and that is what I set about doing. I quickly discovered that each thing, whether it was an old window, bathroom tap or roof tile, brought with it its own set of associations which I was able to use and manipulate. When I say associations, I mean the memories and experiences each of us store in our heads in relation to the world around us.

At one stage during my teens I’d wanted to become an architect, so architectural structures, or discarded bits of architecture, feature frequently in my work. I also try to bring ideas of environmentalism into my sculptures, although this is a theme expressed, for the most part, through the use of certain found-object combinations, rather than any direct narrative.

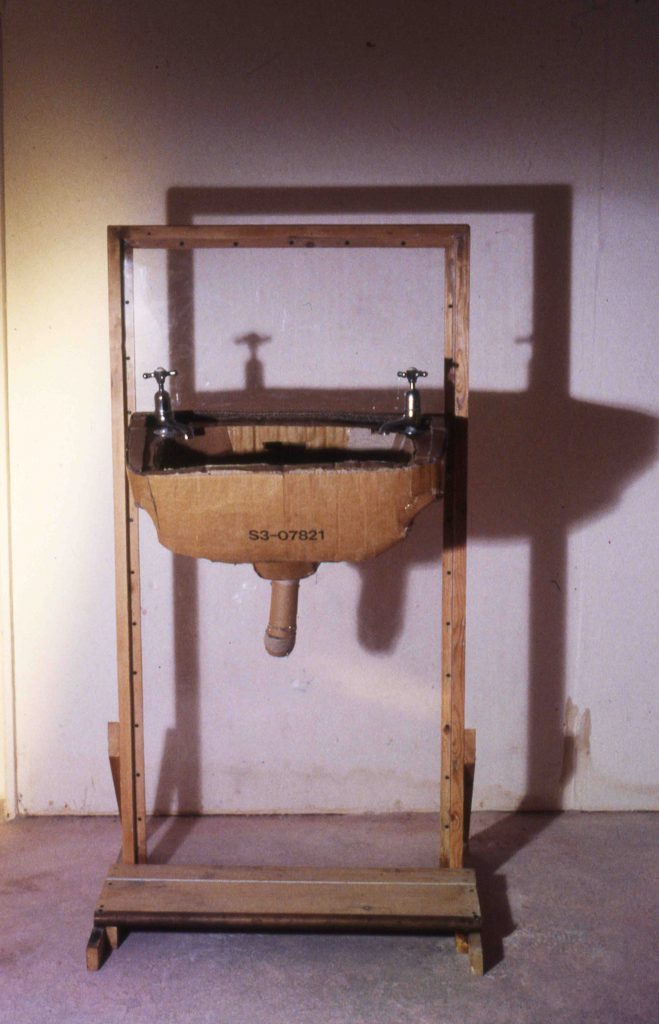

Sink On Wall: Thomas: “The sink is cardboard, made to the exact dimensions of a real sink. The taps are from a skip. Most of the wood was recycled too.”

The Dingy Dilemma

There are many sculptures I could talk about as examples of what I try to do, but there was one in particular which proved to be a turning point for me, for it forced me to focus on what I did and didn’t want to do with my work. It was in my second year at art school, that I had an idea for an enclosed sculpture which would be large enough for people to get inside. My initial sketches of it showed a sort of wooden barrel, or hogshead structure, punctuated by portholes and decked out with velvet button-backed seats. I didn’t want to make something from scratch, so I began looking for a wooden dingy and, through a contact, located one at a local boat yard. Its bottom had rotted away and had been removed for renovation by the owner, but the beautifully lacquered wooden sides, seats and rudder enclosure were all perfectly intact.

I had it delivered the 20 miles to the art school back yard on a trailer and set to work cutting some plywood to replace the bottom. I remember at least one student asking me why I didn’t restore it and use it as a boat. I think they were just looking for something flippant to say, but the first part of the process was to restore it, for I really wanted it to continue being a boat. After that, though, I intended to transform it into something else by adding other elements.

When my sculpture was finished, it had an entrance platform, seat and welded steel hood, and proved a hit with other students. When I arrived in the morning, I’d often find a fellow student sat in it, chatting, and enjoying the experience.

There was then a project set up between the photographic department and ours, with the intention of benefitting both sets of students. The photographers would learn to serve the requirements of a client, and how to capture the essence of a 3D object, while we would find out how 2D specialists saw our work, and represented it. First the photographer would do it their way then we’d do it ours, while the final shoot was supposed to be a coming together of ideas. I was paired up with a high-flying chap who eventually landed a 1st Class Honours Degree. He saw the boat sculpture as having a serene quality to it and suggested hiring a nude model pose inside. I could see his point – the structure of the boat’s base formed a cross and, as it stood up on its stern, its outline was like a cathedral arch – but in retrospect I think he was really more into shooting people than objects.

The photography tutor in charge said, “We’ll, it’s your sculpture, why don’t you pose?” I found myself agreeing and so began my nude modelling career. Impressed by my ability to lie still and look naked, another photography student later hired me to pose for his degree show work, but that’s another story.

Anyway, some days after the initial meeting, several other sculpture students and I hauled the boat from our studios in the basement, up to the photography studios several floors above where the photographer waited. I assembled the three main sections, took off my clothes and, without too much embarrassment, completed the session.

Thomas: “Satisfied that all was legal, this police man took part in our photo session…”

Going Public

For my turn I decided to exhibit my sculpture in a public area in the middle of the city, quite near the market. The space had to be hired, so I made an appointment with the relevant person at City Hall and completed the paperwork that granted me the right to use the space on a given day. I also met with a local reporter and explained that on this particular day there would be an interactive art event involving the public. My idea, you see, was to have a variety of people sit inside the sculpture, making use of the seat I’d constructed.

A mature student who owned a truck was good enough to get in early and help me transport the boat to the market location, and a friend was on hand to take some alternative shots of the goings on. The photographer, on the other hand, was nowhere to be seen. The guy from the press turned up on time however, looked rather unimpressed with the lack of activity and then went. It was an hour and a half before the photographer came bounding along, eager to get cracking.

When things did get going it was great fun. The photographer, like all successful ones I have worked with since, had the gift of the gab, and was soon involving every passer by he could find. In terms of representing the object, he was a little too focussed on the people and not enough on the sculpture, but at least the shots he later passed on to me showed how people interacted with the work.

I’d planned to be on site most of the day, but after an hour or so the photographer made his excuses and dashed off, leaving us without the theatre of photography to sustain a crowd on what was quite a rainy day, or the extra pair of hands for packing everything up and transporting it back to the basement.

Being the owner of the artwork, I somehow ended up doing all of the planning and work for the supposedly collaborative third shoot. The idea this time, on my part at least, was to place the work in a location that would incorporate the photographer’s associations and my ideas on how the object’s apparent meaning could be transformed by its location. I set up a meeting with the head of the city’s cathedral, who turned out to be a very ancient but affable chap, and got permission to install the sculpture in the cathedral cloister. Papers and agreements were signed, a date was set and I managed to enlist my friendly truck driver into helping out once again.

On the day, once again, the photographer made sure he arrived after all the hard work of setting up was done. His shots this time were disappointing. He was so seduced by the cathedral that he became obsessed with getting the whole spire in shot, and so the sculpture was little more than a tiny object in the final shot. From the point of view of showing the work, its detail, three-dimensionality, materials and so on, the pictures were fairly useless, although the cathedral looked good. Fortunately a friend of mine, who had studied fine art himself, had come along to help with the project and he took some much better shots. We shifted the work from the centre of the cloister into the arcade walkway and set up a number of alternative views, some which included curious members of the public.

I’m not sure if the official photographer learnt anything from the experience but I certainly did. And what I learnt was that I wanted my work to be generous. What I mean by that is that I wanted it to give a lot to the viewer. Some work, for example, is so introverted that only art scholars and critics can find anything of interest in it, but I see little value in adopting a visual language that excludes the general public. Having the public – who unsuspectingly stumbled upon the boat in the city centre and at the cathedral – interact with the work, showed me how important that side of art really is.

I still want my work to offer something to those people who want to delve deeper, but I also believe that art is a failure if it doesn’t go out of its way communicate and engage its viewers. To put it another way, you can’t expect people to want to find out what ideas are behind a piece of work if, on the face of it, there is nothing to immediately enjoy about it.

In the cloister. Thomas: “This is one of a series of shots taken by Paul McNeil, who helped me set the boat up at the market and in the cloister.

Thomas: “This was the shot taken by the photographer. A nice view of the cathedral, but not much use for showing a piece of 3D work.”

The State Of Play

The boat sculpture was a real game changer for me. I knew I had made a really good piece of work which would be hard to improve. Apart from one person, who thought I should have been ‘braver’ and cut the boat up (cut it up or turn it upside down are the stock suggestions you tend to get quite frequently at art school) everyone thought it was a great success, and I could see the tutors marking me out as a potential star graduate. I knew that all I had to do, from there on in, was get more and more boats, and experiment with the theme. I’d found my niche – my thing, my theme – and everyone would have gladly accepted it if I’d just ploughed that particular furrow for evermore.

Nevertheless, the mantra of the department head was that art was all about experimenting, and that even the final degree show was not an end, but just a snapshot of where you were at that point. I agreed with that wholeheartedly, the only problem was the tutors didn’t mean it literally. What they really meant was that you should find your theme as soon as possible, do it over and over, never deviate, but feel free to experiment wildly within those narrow parameters.

Bearing that in mind, I could see that doing variations of the boat over and over would have been an easy way to get through with a top mark, but it would have meant nothing of any value to me. There was the recycling element to the work – using an old boat, banisters from a staircase, tiles, and some old wood – but it wasn’t a clear expression of any particular idea. It looked nice, it felt cosy, but that was about it, and I had no interest in repeating it to please the tutors.

So, instead of heading out to the yards in search of another wooden dingy, I began experimenting with all sorts of found objects, trying out ideas without actually completing anything. I was determined not to fall into the trap of making something that was aesthetically pleasing but lacking in meaning.

I’m pretty sure most of my ideas were lost on the tutors. They seemed perfectly happy with work which was about form, colour, materials and structure and nothing more. I don’t believe any of them cared much for work which had something social, or political to say, and that was disappointing. The fact that I had several main themes running though my work, and particularly my final show, and that those themes intertwined with one another, simply baffled them.

In terms of ideas alone, the piece I was most happy with was called Ashes to Ashes. I had got hold of a large oblong block of good quality limestone and carved it to resemble an army-style petrol can with handle and cap at the top. From my study of geology at A-level, I knew that limestone was formed from the shells of billions of marine organisms. So, I mixed up some lime mortar, chiseled recesses in the can and cemented in a number of ammonite fossils that I had collected some years before. Of course, petroleum is a fossil fuel, meaning that it is created by the bodies of tiny creatures settling on the beds of oceans and lakes and being processed by pressure, heat and other actions.

I mounted the sculpture on a plinth, which was actually a large metal oil drum, which I painted black to contrast with the pure white limestone, and to represent the colour of oil.

That kind of internal logic and humour always appeals to me.

Ashes To Ashes. Thomas: “The limestone already contained fossils, but I added some large ones of my own, take from Oxford Clay. I cemented them in using lime cement for a good match. The paint on the barrel is oil based.”

After Art School

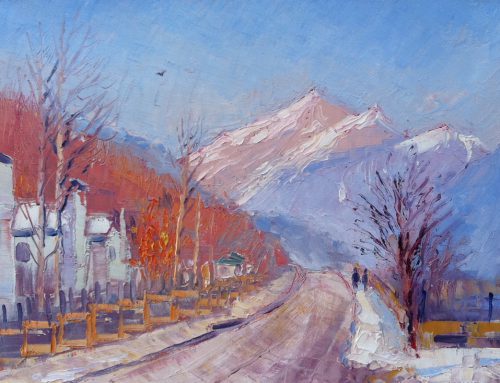

In the years since art school I have continued to make art, but the mediums I have used have changed according to the nature of my ideas. It seems that not only was I unable to restrict my sculpting so that it plundered one single narrow theme ad infinitum, I was also unable to restrict my creativity to sculpture, or even fine art for that matter. My head is usually bursting with more ideas than I can keep track of, many of which are simply not sculptural. I have spent a lot of time working on musical ideas, written works and design ideas, for example, and often turn back to painting and drawing if they seem to be the right way to proceed.

In terms of commercial success, this is not the way to go, as people want to be able to measure, track and categorise your output, but I don’t see the point of having commercial success if you can’t be artistic. This is why, for the most part, I have sought to earn my money doing other things, as most artists do.

In Part 2 Thomas Flint describes how his working methods enabled him to produce an overseas exhibition from scratch in less than a month, using discarded materials and just a few basic tools.

Part 2 of Making New From The Old can be found by clicking here: Part 2

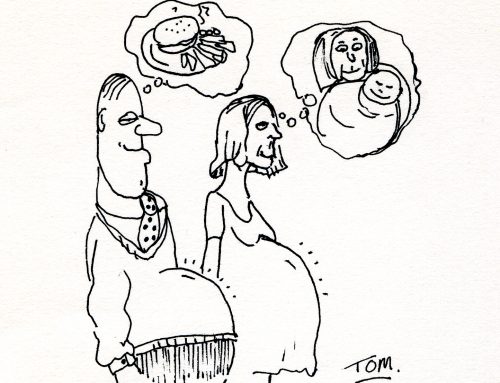

Rocket man!