In Part 3, Rick talks about the last years of Sinclair Research Ltd before it was bought by Alan Sugar and why he set up his own industrial design company. Rick also explains the difficulties of presenting ideas to clients, quoting for jobs and dealing with market expectations.

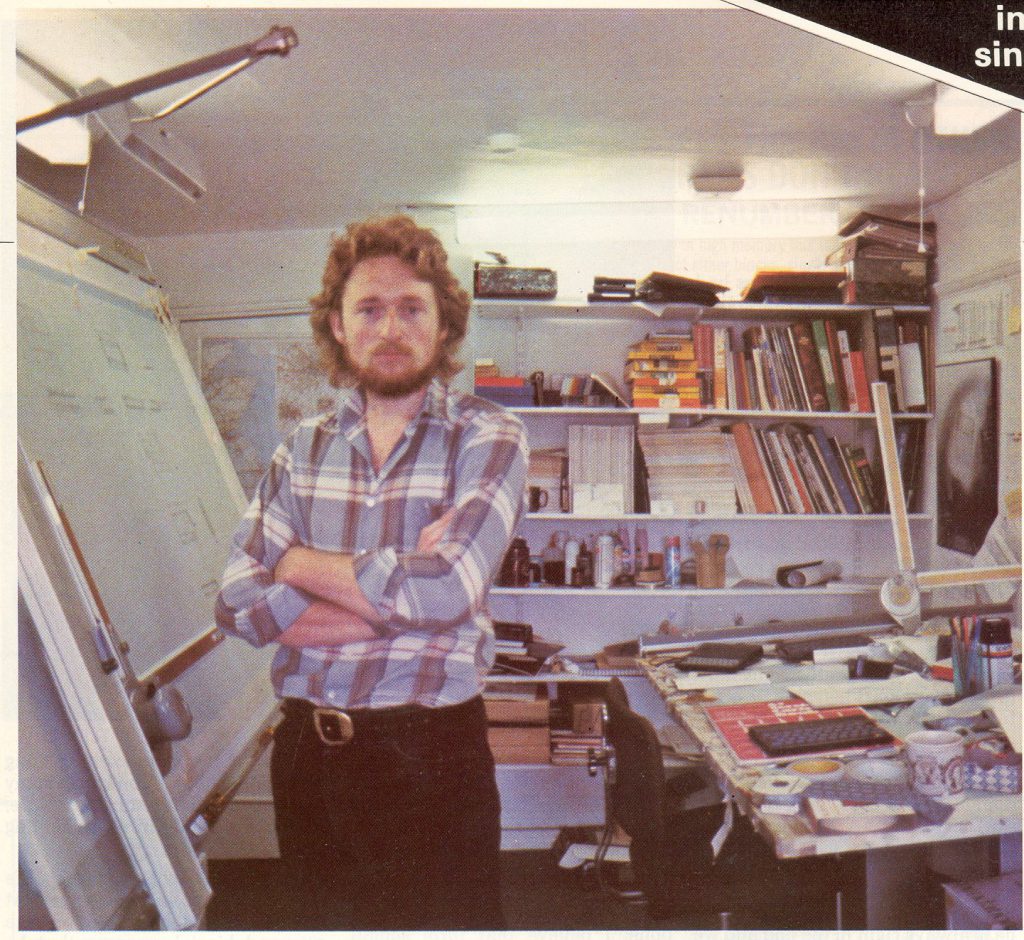

Rick pictured in the early 1980s

Leaving Sinclair Research

Several years after the start of Rick’s employment at what was to become Sinclair Research Ltd, the company mushroomed in size, thanks to the success of products like the ZX Spectrum. But by the middle of the decade it was struggling again, prompting Rick to go it on his own. In 1986, Rick set up his own company called Dickinson Associates, carrying on his work as an industrial designer. He describes the situation leading up to his departure.

“I had a fantastic time working for Sinclair. There were times when I was literally reduced to tears through frustration, not knowing how to get out of a difficult situation, but I learnt that if you are organised you can overcome any problem.

“But there came a time when the company had grown hugely and wasn’t the sort of company that it had been. There was just meeting after meeting and I felt that I was never getting any work done. It’s fine for managers because that’s what their job seems to be about, but if you are a designer or an engineer, you have got to design or engineer something, and that doesn’t happen in meetings. In fact, you come out of the meeting with even more problems! And meetings are very easy. They are quite pleasant; you have coffee, it’s relaxing and there’s no commitment, really, so they tend to become more prolific and less and less work gets done.

“Eventually this culminated in me approaching Clive. He was spending more and more time in London instead of Cambridge, working on other projects; getting the C5 going and all sorts of things like that. I just asked if I could meet up with him some time on a personally matter.

He said ‘Sure, just come round to the house for breakfast. How about tomorrow?’ So I met him at the Stone House and we sat in his kitchen. He said ‘Well, what seems to be the matter?’

I said ‘I don’t really know how to put this politely, so I’ll just say it the way it is. I just don’t like the company any more and how it has become. It makes me really unhappy with my work and I’m not sure what the solution is.’

“He said to me ‘Don’t worry, Rick, I don’t like the company much either. Don’t tell anybody, but I am setting up another company that’s just me, Dave Chatten and Jim Westwood. We have a new product idea which we are going to do and the headquarters will be in my house.’

“I must have elaborated at some point about how difficult it was working in the company because Clive said ‘Why don’t you get a bit of peace by working from home half a day, half a week, or whatever, and spend the other half at the company office?’ so I tried that out. I converted my garage at the bottom of my garden, moved my drawing board there and started working. It was very successful and my productivity improved enormously – I was actually getting work done!

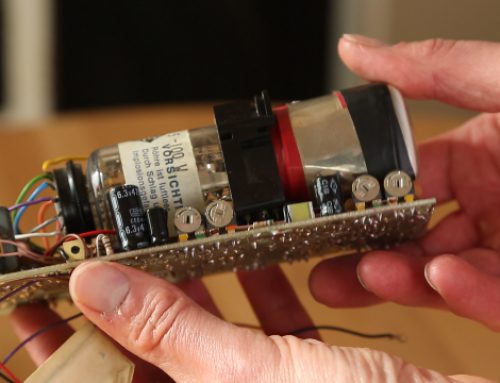

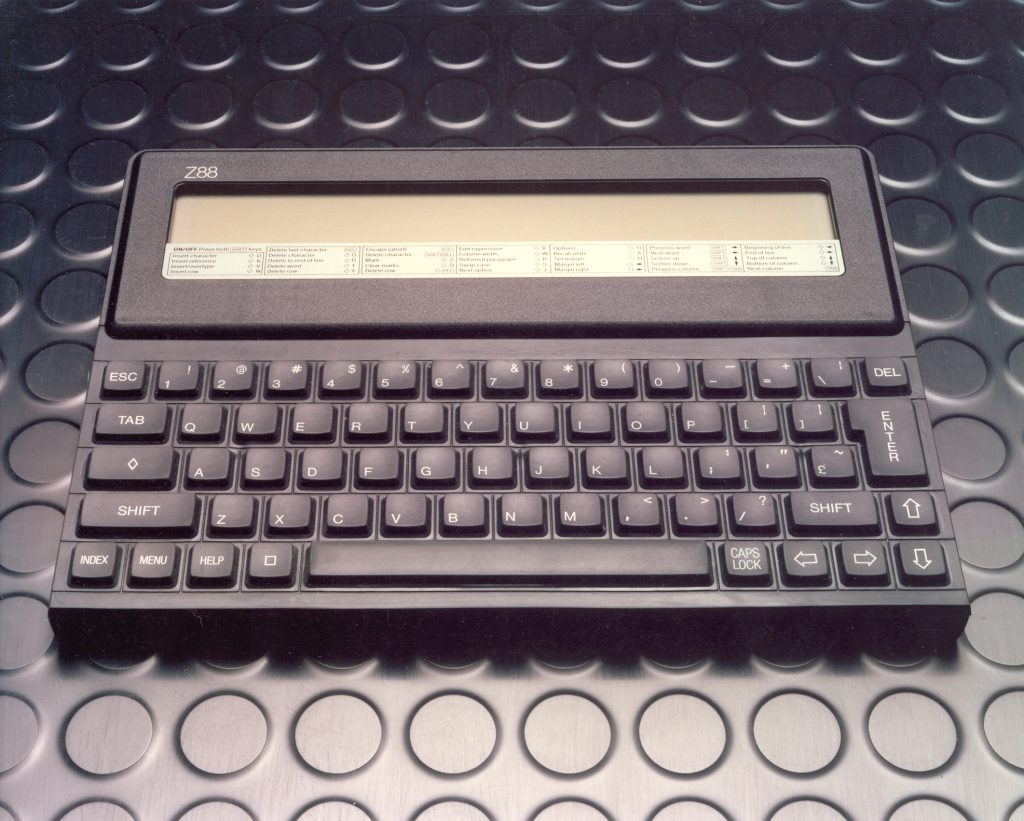

“I was still on the payroll, but then a round of redundancies were announced which was pretty dramatic. After the first round, a number of people set up businesses and asked if I’d help them with their industrial design, so I had a few small jobs from people who had left the company or were made redundant. I also began working on Clive’s new project, which was the Cambridge Z88, as oppose to the ZX80. It was the world’s first laptop, a fabulous product. Then Alan Sugar came on the scene and he eventually bought the company, but by then I’d gone freelance.

“Once Alan Sugar had bought the business it was finished. Everyone who was left lost their jobs. Then, possibly a year later, I had a phone call from Bob Watkins who was Alan Sugar’s technical director. Bob asked if I’d be interested in helping with the design of some of their products.

“The Z88 was behind me by then so I did Amstrad’s first portable computer, or luggable, as they were called in those days, and completely changed the way they went about designing products. Amstrad had a graphics department which tended to visualize whatever they thought was the front of the product. If it was a television that was quite simple, but with other products like computers, they would just visualize a birds-eye view of the keyboard, and maybe a front view of the box that the monitor sat on, and that was it. The visuals were just artist’s impressions but they would be sent off to their factory in China, or wherever it was at the time, along with all the PCB designs and working specifications, and the factory would actually do the engineering design. Unsurprisingly, I think they had had a lot of nasty surprises doing it that way and they wanted a bit more certainty.

“So I said ‘This is how we did it at Sinclair and it’s quite a normal way of doing things. Why don’t you go into it gently? So, for example, when we do a visualization, let’s be sure we’ve got all the main things that we can’t move around much and get those in the right sort of order. That gives you the right shape for a particular product – if it is to stand up on its end or on its side – and then visualize every angle of that, so you can see where the connectors are coming out; you can even see it from underneath where the feet are; think about the cooling and the cooling vents and the effect that might have on the product.’

“So we went though that and next I said, ‘What you really should do is make a model,’ but they had never made a model of anything. I remember the model was really expensive and cost more than my design fees to get them to that stage. But when I turned up with the model, Alan Sugar was over the moon and I remember Bob Watkins kept saying to me ‘I’ve worked with Mr Sugar all my life and I’ve never seen him so happy.’ I thought, ‘Wow!’

“A few weeks later Alan Sugar offered me a full-time job, but unlike The Apprentice, I turned it down!

“It was interesting experiencing the contrasting styles of Clive and Alan. Clive was absolutely into ideas, technology and innovation and finding new ways of doing things. If Clive needed a bit of technology that didn’t exist, he’d invent it and make it himself, whereas Alan simply saw more economic ways of reproducing what people were already making. So he would use off-the-shelf mainstream technology. I’m not saying for a moment which approach is right and which is wrong, I’m just reporting. But with Amstrad, on the occasions when I thought that they had made the right decision, for me it wasn’t actually for the wrong reasons, which was always disappointing. It was just chance really.”

Rick “The Z88 was only possible by ditching the Sinclair cathode tube display for an LCD, and the microdrives for solid state memory cartridges.”

Perception and Reception

Two decades on from the British computer boom, Rick is in a position to reflect on how the industry has changed, and what personal qualities an industrial designer must have in order to ride the changes and get on in the fast-moving world of production.

“It really is a scary world now,” insists Rick. “You’ve got to understand people and be a bit of a showman, although that doesn’t mean that I am. You’ve got to understand psychology –what people are thinking when they look at something. And you’ve got to understand expectations.

“The first time I realized this was when I’d made a model of the Sinclair QL computer. Luckily for me, Clive really liked it and we even got an Italian design award, which I was so pleased about, but as soon as Clive saw the model, the product was ready as far as he was concerned. He said ‘Let’s launch the project and get a marketing campaign going.’ He’d seen a model and it was real enough to him. I don’t mean he thought it was a production item, but he could see how it was going to look and thought that it must be close to being ready.

“These days you still have to be really careful what you show to people because with computer tools you can arrive very, very quickly at something that appears real, where the danger is that there is nothing real about it. It’s unmanufacturable. You haven’t even thought about what it’s going to be made of, whether the bits will fit – you don’t even know what the bits are! You’ve done the easy bit; you’ve done the outside without thinking about anything else. But the finished thing could never be like that because it’s absolute science fiction. So you have got to be very careful.

“What you show often depends on whether you are working for someone who is well practiced at going through the design and manufacturing process, or someone who is going though the process for the first time. An entrepreneurial start-up company may employ experienced staff but you might find that the CEO is the entrepreneur and is not experienced in the design and manufacturing process, and doesn’t have appropriate expectations.

“And you need to know that so you can make the process of design specific to their needs and lack of knowledge; because you do design together, there is no question about that. You have to carefully decide what information to give to the client, and in what way, as you go through the design process. It could be a meeting on a daily basis or one every now and again.

“How you take them through the reasons why you’ve arrived at a particular result, especially at the early stage, is important psychologically. Showing work-in-progress can be a disaster. Some people ask if they can come round and have a look and I say ‘Not until its finished,’ because it’s the last few minutes that it really pulls together. I can pretty much guarantee they won’t like it if they do because it’s not finished and they won’t fully understand what they are looking at.”

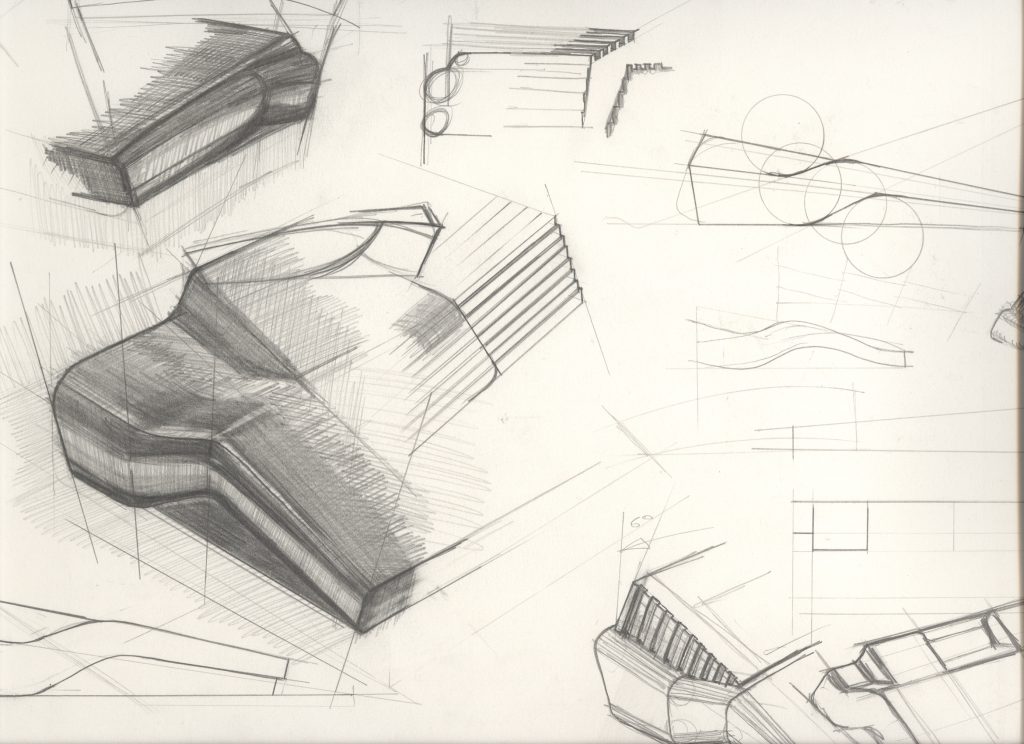

One of Rick’s early drawing for the Sinclair QL design.

Making Models

“We start making models quite early on but most people don’t understand what a prototype or pre-production model is – even people who are in the industry. It can mean different things to different people so the terminology can be critically important.

“You make a model where you have a vague idea what’s going on inside but want to give someone a flavour of the outside of the design. You are saying that it could be in this vein, plus or minus 10 percent of anything.

“There are lots of ways of making models. You can make a model that’s quickly machined from a solid block of material so that all the detail is there but it is left unpainted. Then you support it with a 3D rendering and that works incredibly well. It is very quick; you can get there in a day, so for a few hundred pounds you can see it and feel it. Obviously if you press the buttons they are not going to go down and you can’t see the display because it’s just this blank material.

“It is so many orders of magnitude harder to go to the next level of model where the functions still don’t work but it really does look like the real thing, with graphics and a clear window for the display. It takes weeks and weeks of design and model making to go to that level, so in general we don’t go there.

“There is an intermediate level where you take the solid block model and just paint it, but as soon as you do it loses the subliminal reality and stops looking like a visual prototype. When it is made of cardboard and unpainted, everybody knows they are looking at a cardboard model. If you make it out of cardboard and paint it people think ‘Well, that’s crap.’ They can see the K from Kellogg’s shining through the black or the rough edges of the cardboard. People start assuming that it is real and when they do the method you are using to make it won’t satisfy their expectations. They will be disappointed with the finish of the edges and the micro detail. You can never equal the quality of something produced on a mould tool with any other method, so, if it’s a prototype, keep it crude and don’t paint it.”

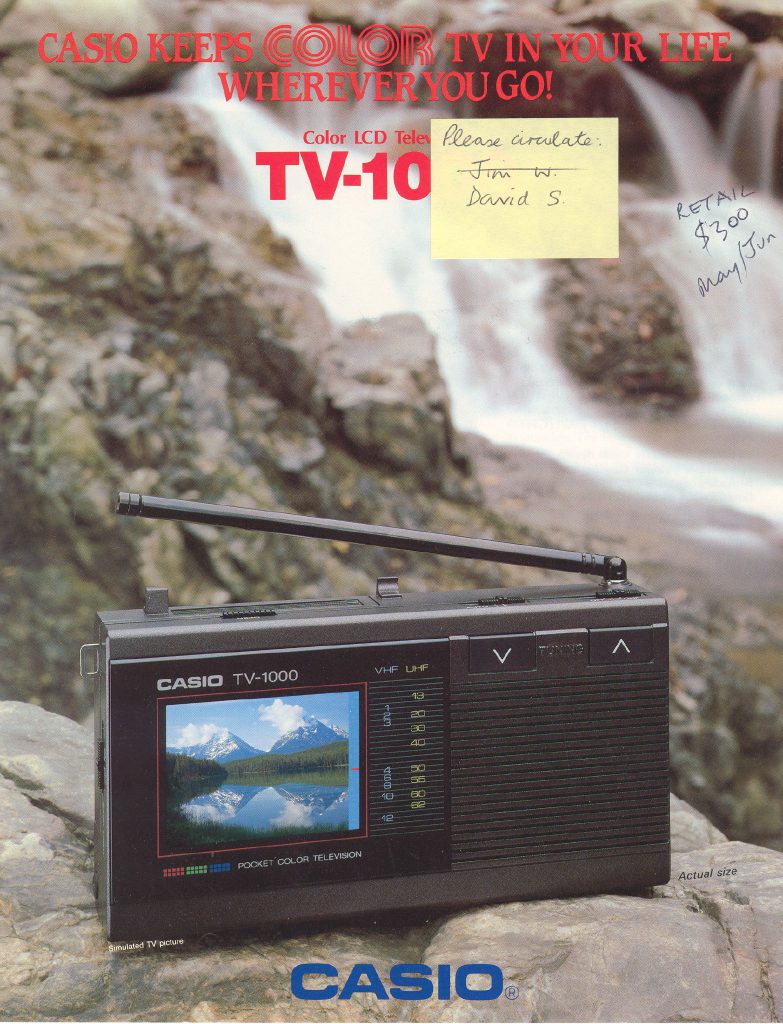

Rick: “A range of models I made for the pocket TV80 design development, with the production item back middle.”

Rick: …”and how the Japanese copied it – as they always did!”

How Long is a Piece of String?

Given the complexity of the task an industrial designer faces, it is easy to imagine how fiendishly difficult it must be to quote for a job. Understandably, the client is still going to want to know how much the designer’s services are going to cost, but it seems likely that few clients really appreciate the enormity of the task. Rick explains how he finds the situation.

“I learn all the time and I’ve had some really funny experiences recently. The client definitely doesn’t know what’s involved with the job, which is why they are asking you to do it. You don’t know at the start, and it’s a long time before you are going to know what it’s like, what it’s going to involve and how much time it will take. But you have to give someone a quote.

“What actually happens is it is not a discussion about your hourly rate or how many people are going to work on it. Typically, you are given a business plan and the Gantt chart that shows when the product needs to be in production and you work back from that. So you already have the time-line and it is just whether you can do it in that time or not. No one even asks you whether it can be done; it’s already an approved business plan and has had the rubber stamp from someone up high.

“I think there’s a cost for a job. If, for example, you have three plumbers come round and quote for a job you get feel for how much it might be. Their quotes are not going to be too different and I think it is like that in the design industry. If there are several of us putting in competing quotes it’s often amazing how close we have all been on price. Some designers are much faster than others, which means some are very slow, but because there is usually a time-line or schedule to adhere to, the question is usually ‘Can you do it in that time?’ Time is nearly always of the essence.”

It is clear from what Rick says that the relationship an industrial designer has with his clients is very important. An experienced company director is likely to appreciate the complexities of the design process and set their budget and production schedule accordingly. However, there are many circumstances in which the situation is very different, as Rick explains.

“There might be a client who we have worked for who gets taken over by another company or a new MD or CEO comes in and wants to make a clean break of it all and improve things on his watch. He thinks ‘I know, we’ll spend less money on R&D!’ It’s preposterous really. If people are happy with your work and requirements, whatever they might be, why change?

“But quite often you find you are competing with other designers, even though it is a long-established client, simply because the guy at the top has changed. Tender is put out and if you are lucky you are told about it. You know for a fact that everyone tendering for that job knows it is new business so they are going to come in with a loss-leader price, and you are competing with their quote regardless of whether or not they can do the job. There is no telling what kind of experience it is going to be for all the staff having to work with the new designer so it really is an enormous unknown for a company.

“But you know that whatever you were going to quote has now got to be a lot less. You’ve always got the option of quoting your normal price, but you have to ask yourself if you mind losing the job, which is probably what’s going to happen if you do.

“One time I was asked to quote for a job and it took me two days thinking it all through. You’ve got to design it in your head quite thoroughly just to get a feel for the magnitude of the task. You have to ask yourself, ‘Is it an OK or mediocre job? Are they going to be a nightmare to work with, constantly changing things or are they going to be OK?’ There are all those kinds of human issues to think about.

“When I’d thought it through I looked at the numbers and thought ‘That’s a lot of money, they’ll never pay that. OK, I’ll halve it!’ And, of course, once you’ve done that it makes nonsense of all the stages that you’ve calculated. So what do you do; just half all those stages as well? It all becomes nonsense. So I put my half quote in, was summoned to a meeting and they said I was over budget. I said ‘What do you mean over budget? You’ve asked me to quote so that is the budget. Why didn’t you tell me you had a budget? Then I could have said “Yes, I can do it for that,” or “No I can’t.” You’ve wasted me two days.’ So I’ve learnt that now!

“Businesses are changing all the time and the world is changing how it does business, so what was appropriate or applicable 10 years ago isn’t now. It’s just trying to keep tabs and aware of how things are changing. These days I always ask if they have a budget and to tell me before I walk out the door, because it could save a lot of time. I’ll be able to tell if it is woefully inadequate, regardless who designs it, or if it’s sufficient.”

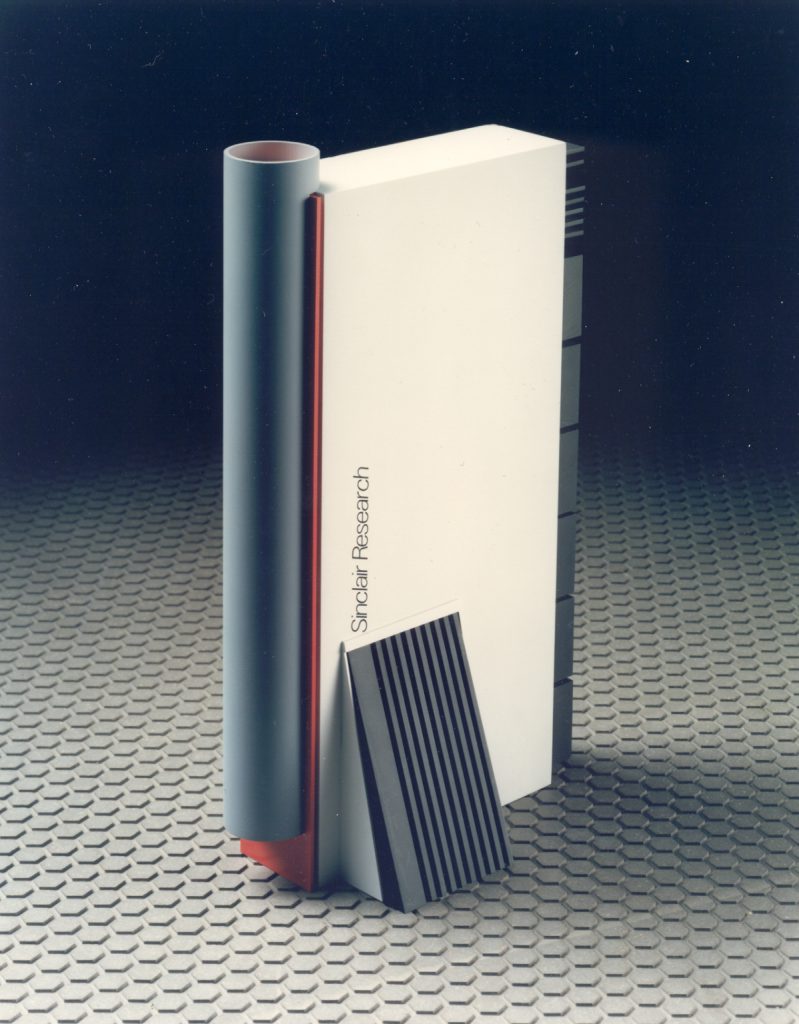

Rick “Concept model of a vertical computer for next generation QL – desk footprint space was becoming topical, so I stood it on its end. The rest featured serious thermal managemnet and cable routing, and the heavy power supply at the base to help stability – common sense really.”

Designing Tools

A lot has changed since Rick began studying to become an industrial designer. Not only have the products become more complex, so have the tools that the designer is expected to use in his work. Rick explains the pros and cons of using the industry standard software for industrial design.

“It’s very hard to design with computer programmes because they are cumbersome, awkward and non intuitive. You can’t just change something a couple of millimetres. Doing that could create several days work because of how the change affects the rest of the virtual model. The order which you put features into a model is important because if you change something that was established quite early on in the model building, all the features added after that die. They just don’t exist anymore. So they are very unwieldy tools and incredibly time consuming. I don’t think you do much design on them actually. They’ve got a long way to go.

“We use PTC Pro/Engineer which is considered to be the industry Rolls Royce. Bosh or Motorola will have Pro/Engineer. We chose it because it was considered to be the best and, at that time, a lot of manufacturing and tooling was done in China and China tended to prefer Pro/Engineer. Not everyone uses Pro/Engineer and there are lots of other systems about. Pro/Engineer is not very good at rendering and is not especially user friendly, but you have a terrific amount of control.

“From Pro/Engineer, we export 3D files and support those with 2D drawings. A 3D file doesn’t tell you everything about a part, so you’ve got to support it with drawings that describe basic things like colour, texture and material. If there is a hole that needs a thread, the drawings explain what thread to put in. They will also say if anything needs specific tollerancing beyond the normal bounds.

“If it’s an injection moulding, for example, there is an industry accepted tolerance range, which means a part can be larger or smaller than a certain dimension, but you may have parts of your design that need a particularly closely-monitored tolerance. You can’t put that in a 3D model, you can only state it on a drawing. You might say ‘I don’t want this hole to be larger than 10mm but it can be as small as 9.8mm.’ It’s vital information to the manufacturer because it will dictate how they go about making the mould tool to give that level of tolerance on that one feature. So you send a set of 3D files and drawings off to the tool designer and he’ll prepare drawings for the tool maker.”

Before booting up Pro/Engineer, Rick starts working on his ideas using a pencil and paper, sketching fast and often: “The life of a sketch is just seconds or minutes then it’s on to the next one, so we have masses and masses of paper. Even when you are sketching in the early days of a design project, you are thinking about materials, how to shape them and how you are going to assemble the parts. I’ll be thinking about the ergonomics and asking myself what things I might have forgotten about that are not obvious. Quite often I’ll come across some very early technical issues that I want to check with a manufacturer. I might ask if it can be made a certain way and if they say no then we have to pursue a different route.

“Then we might make a model with a material like Styrofoam, with which we can create shapes very quickly, just to get an understanding as to whether we are going in the right direction with a particular shape.

“If we don’t take that approach then it’s into the computer. We can very quickly model the main attributes of what makes the thing function before any design or engineer gets involved. So if it is a mobile phone, it’ll be an idea of the battery, display, keypad and camera. The model gives us a feel of how the product naturally is with those four main parts assembled together, before starting to manipulate that basic form.

“Interestingly, the drawing board I used at Sinclair followed me for years, and even when we’d moved over to CAD we still used it for certain activities because it was faster and more intuitive. A problem with CAD is that it can only work in an exact way and to 9 decimal places. Conceptual design, on the other hand, can only exist in the world of approximation and fluidity – a handy point to note, as too many designs start on CAD and not the sketch book. Purely on the grounds of its size I retired the board fairly recently and it now resides at the Science Museum!”

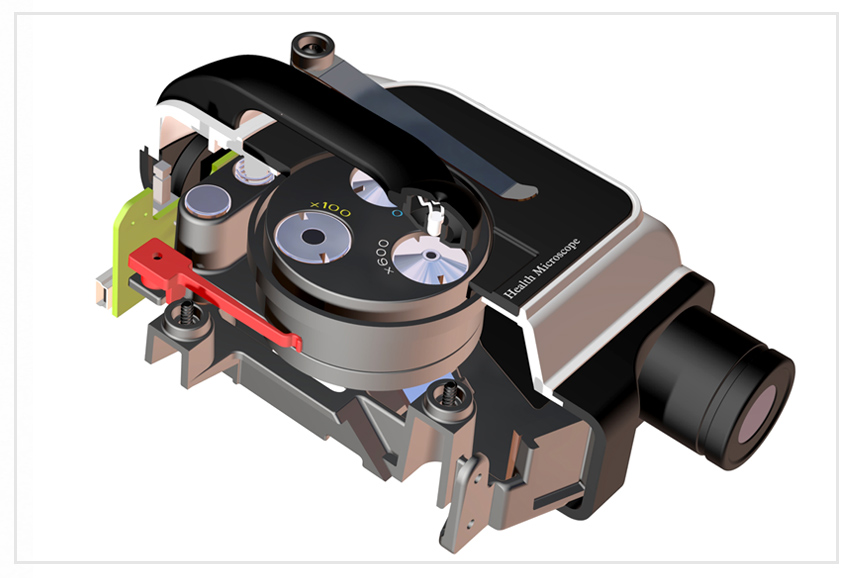

A health microscope design – very complex. Rick: “We use Pro Engineer from PTC, which stands for Parametric Technology Corporation. Being parametrically linked is important as it allows you to create relationships that remain constant. That can be applied to the gap around a connector, or a set of parts forming a single sub-assembly in relation to another area.”

So, What’s it All About?

If one thing is clear from what Rick has said, just looking at a finished product tells us very little of the story of its creation. Someone not party to the design process can only hazard a guess at the reasons why something ends up the way it does, and even the designer themselves may only know a part of the story. Perhaps that is why, after more than 31 years as a professional, Rick seems fascinated with industrial design. Every new project poses a challenge, as if it were a puzzle waiting for the pieces to be found and put together.

When trying to decide which pictures to use to illustrate this interview, Rick points out a 3D drawing of a health microscope and explains that every gram of material shown in the cross sectional view was designed by Dickinson Associates. It is an incredibly complicated looking object with many interlocking parts and is clearly the result of a very long and arduous process. Even for Rick, pinning down exactly what that process is has proved to be very tricky – there are just too many variables involved to come up with an all-encompassing description. Nevertheless, he does find a few points which seem to sum it up what it is essentially all about.

“You’ve got to understand the most important thing, which is the end user,” concludes Rick. “I think the industrial designer is very often unique in the team in that respect. The software guys have an element of that and maybe the marketing or sales person involved in the team do too, but no one else embraces all the disciplines that combine to make a product and affect how the user relates to it. I don’t think are as many roles that cover as many disciplines as industrial design does.

“Understanding the user is your goal and it’s a very clear goal. We are very goal orientated and very focussed. I find that, very often, the other disciplines get quite distracted or have very niche goals. It’s as if they are one gear within a gearbox and only have to mesh with the adjacent gear.

So you are a bit of a product champion really. This is what Clive did really well; he was a product champion. He would see the bits that were important to the end product from the user’s standpoint.

“A product is going to be used by a human being so you need to know all about that human being. That is the constant reference point. Is it a high volume consumer product or low volume medical product.? What is the point of sale? Is this a product that somebody will go into a shop and choose for themselves, or one that will be issued to them, like a soldier’s personal mobile radio? The way that the end product is going to be used and how it arrives with the user can differ and these considerations set you off in very different directions.

“We take apart competitor’s products to try to understand why the designers did what they did in one area or another. Just because someone has done something, it doesn’t mean that they have done it right or for the right reasons. You are looking at their mistakes as well – the blind alley they led themselves down and got stuck!”

“High volume products are particularly difficult because very often there is a lot of distracting activity like specmanship, by which I mean aiming to have the most impressive spec. They will want their product to have more knobs or buttons, a little bit more power, or a slightly bigger and brighter display than the competition, but I ask ‘Why? Does that relate to the functionality? Does your ergonomic study say you need another button? What is that extra button for?’

“They might answer ‘Well, the competition have got 10 buttons so we want 11.’ You might think that is laughable but that is very often how it is. It’s quite a sad world in some ways. People are forever trying to out do one another and it’s not about product design. It’s about other things, floated under the heading of the product being better than the last. It’s driven by people wanting to make a quick buck for the least amount of effort.

“Often you find it is not better and you actually preferred the way a particular function of the last generation product worked and wish they’d retained it. It’s a bit like when you update your computer software. They’ll have improved some thing but spoilt something that was right. You get it in automotive design as well. Next year’s model of the same car: it’s different, not better.

“Consumers have such enormously high expectations because there are now so many fantastic products that do fantastic things. And it’s so difficult to meet that. People are seduced into buying stuff they don’t really need. If there is a requirement for a product then there is going to be a right answer for it and definitely lots of wrong answers.

“We have a lot of battles with sales and marketing people who have these various inputs because they think that the consumer wants this and that, when actually the consumer doesn’t. If you go into a supermarket and walk down the yoghurt isle there might be 53 flavours of yoghurt, but do you really need that many? Like ice cream, deep down you know there is only one flavour. Just because you have created a variety it doesn’t mean it is as good or better. It could be a whole lot worse.

“I think that the way a product comes about or is born is changing. In most cases it has come from somebody in the company seeing a market opportunity of some sort, either because they have seen a piece of emerging technology that could give them an advantage on cost, performance or user experience, or they see an emerging market that isn’t very well addressed currently which they could address.”

The Altio, from Dickinson Associates.

Name of the Game

As to whether he plans to carry on battling with marketing departments, CEOs with unrealistic expectations and the complexities of design, Rick is adamant that he will.

“I just love making things, fiddling about and investigating how things are made. Designers are unsung heroes because in this country there’s no understanding of the role of the designer. It’s a funny profession in the sense that there aren’t enough people who actually know what it is, even product designers themselves. A lot depends on the course they did and why they were attracted to it in the first place.

“I was asked to do a questionnaire on the street once so I thought ‘OK, fine, I’ve got 10 minutes.’ “The interviewer got to a question which asked you to pick the job your father did from a list of options. I looked at the list and said ‘He doesn’t do any of those.’

“The guy said, ‘Oh, what is he?’

“I said ‘He’s a structural engineer and trained as an aeronautical engineer. You haven’t got either of those on there.’

“He said, ‘Oh, does he operate a machine then?’

“And this is the birth place of the industrial revolution! I find it staggering. If you bump into someone at a party there is the inevitable dreaded question of ‘What do you do?’ A really good friend of mine, who worked with me at Sinclair as an industrial designer in the latter years, would say ‘I’m a bacon slicer at Tesco,’ and the questioner would move on.” TF

Part 1 of this interview with Rick can be found here: Part 1

Part 2 of this interview with Rick can be found here: Part 2

Also see the interview with Sinclair electronics engineer, Brian Flint here: Part 1